Watch the Video

This talk on the meaning of the Zombie and on the place of monsters in the world was given at the OCA Diocese of the South Annual conference in Chattanooga, TN on July 27, 2017.

Read the Essay

Source: Orthodox Arts Journal. Reprinted with permission. Click images to enlarge.

By Jonathan Pageau

As Culture Deconstructs Increasingly Perverse Images Calculated to Arouse Desire Fill the Narrative Fabric

We live in a time of monsters. I think you already know that. We only need to glance at popular culture to realize this. At the narrative level of our culture, in our stories we have become obsessed with monsters, with the strange, aliens, with the marginal, with a glorification of exception, of the things that do not fit. Many of us grew up with Sesame Street which taught us that monsters are our friends. But it is no longer just fiction, the monsters have left the dark spaces under our beds, have left our nightmares to come out into the open.

At a social level we can feel and see all around us the growing polarization, the acceleration of what we can only call a strange breakdown, the decomposition of culture, the progressive dissipation of any center which can rally us as societies.

It is difficult not to meditate on Yeats’ “Second Coming” as if the horrific cycle of the twentieth century seems to be on its way towards repetition.

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

This poem of which I have quoted the first part is possibly one of the most known in modern poetry, the most cited. It rings so true because we stand in that widening gyre, at the edge of the world where the wheel is spinning so fast one feels it will come of its axis.

Nihilism and the Cult of Death Lie at the Center of a Culture that Has Lost its Center

And it is here on the edge that we find the zombies wandering aimlessly in a world that is losing its center. Unlike most of his monstrous brothers, the zombie is truly the harbinger of contemporary nihilism. The zombie has no magic, its arrival usually has no clear reason, but rather the zombie is couched in a biological accident, a disease, a plague. Simply an animated corpse, the zombie inhabits the indeterminate space of living death, roaming around in packs, the zombie shows us the mindless wandering of a mindless mob with an insatiable hunger for devouring others, for swallowing life. If the vampire is the monster of aristocracy, the zombie is the monster of the mass, of the accidental, of quantitative leveling. The zombie is the atheist insistence on the illusion of free will. It is an image of nihilism and of idiosyncrasy taken all the way to decomposition.

In almost every major city in North America and Europe they have these events, they call them zombie walks. People dress up as zombies and walk in thousands down the streets, dressed up and made up to look like corpses, shifting around with dead empty eyes and pretending to be the walking dead.

Some of these are huge. If we were generous we could say that it is a Zombie procession we could call it, they’re liturgical zombies if there is such a thing.

The zombie both typifies the mob, while simultaneously the absolute individualism, the absolute isolation of contemporary life, for the zombies in a horde only interact with what they desire and never interact with each other. The trope of cannibalism is a very ancient one. We find it in so many ancient stories. But the tweak in zombies of eating brains is a very powerful one, because it is truly an image of the nihilist. The zombie is a creature without meaning, without intelligence, it misses any forms personhood, and has this insatiable desire which mirrors what it lacks. It desires what it lack, identity, meaning, and this desire appears in that materialist reduction of identity and personhood to a clump of cells up there in your cranium, the zombie wants to eat your brains because it cannot eat the mind, it cannot inhabit the mind.

Strangely enough the desire to eat the living is the extreme perversion of our desire for communion and it is also the distilled image of all our passions, our attempt to fill the unquenchable yearning through our passions always transforms others into commodities which can get us what we think we need. The zombie is both an image of the social breakdown, the person as a meaningless statistic, the disappearance of common values except the overwhelming desire to consume, so also as it is an image of the breakdown of the person itself into an soulless desiring death machine.

There is a rather strict analogy between these different levels of the world. The social breakdown and polarization is to the state what the abandonment to the passions is for the person, and the zombie is both those fragmentations at the same time.

A New World Where Death is Overcome and Beauty Revealed

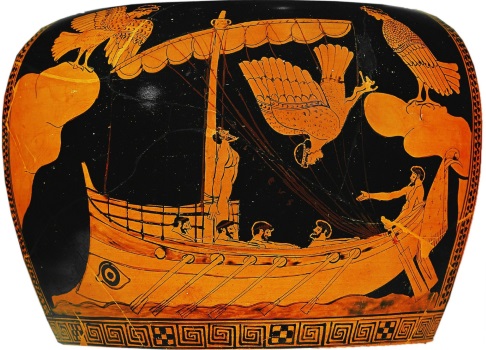

So to pull back a bit. As we look around, As the narrative fabric of the world begins to fill, in quantities that are barely possible to believe, with images of the monstrous — as we feel the world being torn apart by fragmentation and conflict, we are simultaneously as individuals being constantly assaulted by images, images with the purpose of awaking our desires. And we have come to the point where we have often even become accustomed to a constant exposure to the stranger and stranger fringe of desire while being enticed by the siren song to indulge, to give into the waves and the storm and to sink into the mire.

Now as we here, hopefully still hold on to a liturgical world, not the zombie kind, the more refined kind, a world which strives out of pattern and purpose, we can both stand in a church where Christ in the dome is the origin of the heavenly hierarchy of beings. We also know that we can find hesychia in our heart, our center, as a gateway to the divine and as the manager the passions whirling in the widening gyre.

Just like our individual unholy unions with death appear on the edges of our beings where through an excessive attachment to our senses we mingle with our passions and produce our own aberrations, the cosmic monsters lies at the edge of the world, the edge and the end of the world. Those two things, the edge and the end represent the same structure, the same things in stories that we know.

The notion that a movement towards the edge and a movement towards the end are of similar nature is one which is there right in the beginning of the Bible. When Adam and Eve fall, when they are moving away from the central tree, out past the walls of the garden, the limit of the garden then appears as the four faced animal human hybrid image, the cherub, which is also described elsewhere as the mount, the seat of God.

Similarly, as Adam and Eve move out and enter into history, they are given garments of skin, an outer layer of animality, a layer of death to protect them from death.

If your mind is struggling at how a layer of death could protect you from death, just think of a vaccine. This garment of skin is seen by the Church Fathers as all that is added to our nature in the world of the fall, the layers of society, of technology which are the flip-side and in a way of the same nature as our weakness and the passions which come from the world of death. St. Gregory of Nyssa tells us that the hairs on our body are a symbol of death, they are without feeling and dead, and appear at our spatial extremities, the very limit of our garments of skin, just as death appears at our temporal extremity in this earthly life.

The giants in the Bible, those that appeared before the flood were the sign of confusion and mixture wrapped in inappropriate sexual desire. In the Enochian tradition they are seen as the origin of technology and magic and were known to create hybrids. They were full of excess, reveling in conflict, until absolute chaos could no longer be held at bay, and the world was undone in the waters. The ceremony of innocence was drowned in sophisticated, hybrid, non-binary fluid categories.

And in a parallel way the ancients described the world geographically as a giant island surrounded by a vast ocean whose fringes were inhabited by impossible monsters, these signs of the breakdown and confusion of categories which is death, basically the cosmic garments of skin. The images below are based on the descriptions of the far away races the first century Pliny the Elder who died during the Vesuvius eruption which destroyed Pompeii.

Imagine how the great Roman Natural historian Pliny the Elder would have described our own far away specimens, such as the extreme body modifications that can be seen above.

Imagine how the great Roman Natural historian Pliny the Elder would have described our own far away specimens, such as the extreme body modifications that can be seen above.

But I need to be careful, as we stand as it were, possibly on the edge of the world, it would be too easy to point and say: “There are the degenerate ones, and thank God we are safe in the Church.” Like I mentioned, in everything I will be saying in this entire talk, the same chaos which lies on the edge of the earth lies also on the edge of each of us. But what we can do is be attentive and read the signs of the time. How do we make sense of this as we look around us to find the floodwaters rising, how do we navigate through the growing chaos?

Pentecost as the Cosmic Recapitulation of a Fractured/Deconstructed Cosmos

In the back of my mind there is a saying which plays over and over, maybe in the hopes of convincing myself, it is that last promise made by Christ before his ascension: “Behold, I am with you until the end of the age.” And we know as orthodox Christians that in this promise is also implied that Christ is with us until the limits of the world.

Christ is with us unto the bottom of the world, the bottom of death, where he crushed the head of the serpent as he descended into Hades. The promise Christ made as he was about to ascend to the Father is the promise of Pentecost. It echoes the promise of the Spirit we find in the Gospel of St. John (Jn. 14). Pentecost is the possibility of moving in Christ from the top, from the highest place, or else from the center let’s say, until the end of the world, until the end of the age.

It is the Church ablaze, a fire that spreads and consumes until the age itself is consumed but like the burning bush seen by Moses on the Mountain, the Church itself is not consumed. Pentecost is a different type of multiplicity, a multiplicity which is not the fragmentation and decomposition of our times, but it is a multiplication which does not forget its center. In the terms of the Philokalia, as we move into multiplicity, Pentecost is the possibility of the remembrance of God, the remembrance of God even unto death.

The icon of Pentecost presents a cosmic image. The Apostles are seated in an arch, a proxy for the entire Church itself. The icon of Pentecost is one of those icons which though representing an event in the Bible, represents it in a manner that goes beyond the event and becomes a permanent image of how the Church exists in the world. The hint that this is the case is of course how, just as in the image of the Ascension, St. Paul is represented though he was not there in the Biblical account. St. Peter and St. Paul are there as they are in so many icons, as the pillars of the Church, the left and the right hand of Christ. Above the Apostles is the holy fire which descends on them, this fire, separates into twelve, just as the Apostles themselves each acquired tongues of fire, tongues which speak in a manner that can reveal Christ through multiplicity and be heard by all men.

And then, down in the bottom of the icon, is the door which leads outside of the upper room, the outer darkness in which the allegorical figure of the Cosmos holds the scrolls, the fully manifest form of the 12 traditions issued by the one fire, the one Church whose unity is preserved in its multiplicity. Of course the door of Pentecost is the door of the Church itself considered at all the levels of interpretation in which we can understand that statement, it the cosmic body of Christ, but it is also the actual church building, is the road that leads out of the nave into the chaos outside.

In the earlier traditions of the Pentecost, what was presented in the door was not this synthetic image of Cosmos. In the earliest images I could find of the form of Pentecost we have now are from after iconoclasm and they represent simply an open door. Soon what was represented in the door was a crowd of foreigners all with different hats and different clothing, and different shades of skin color.

Just above is one of my favorite versions from a Serbian monastery where the door of Pentecost is actually a window which leads to the outside of the church, and the foreigners appear on the edge of the image.

There is also a tradition from Armenia which portrays a monster in the door of Pentecost, the monster is either a dog-headed man, a cynocephalus, or else it is truly a unnameable monster, a kind of chaotic being with a dog-face growing behind its head.

The chaotic monster can be seen in the first image of my presentation. The first time I saw that image I was startled beyond belief. But as I began to understand the image of Pentecost, I realized to what extent it is a testimony to the totality of what Christianity is meant to be, to the true possibility of God being All in All.

The monster as an inhabitant of the margin is a token of that which does not fit within what we know, cannot be measured in the categories we are aware of. It appears as a freak, as the ultimate unexpected. So the monster is both the encounter with the surprise of the future as we move forward in time so to encounter the unexpected, and the monster is also the encounter with the surprise of the edge, as the Church expands unto the dark corners of the world, but also the dark corners of our own lives.

As the Spirit of God transforms us, for most of us there are always foreign elements, monsters hiding in our garments of skin that act as fuel for the fire of the deification process to continue. And so here in Pentecost, this monster is represented as not yet in the Church but as part of the potential into which the Church can grow, as part of that which can hear the gospel in its language

Just a caveat in case there are any crypto-zoologists or conspiracy types reading this. We always have to be careful when we read ancient accounts, not to interpret them in our rather materialistic frames of genus and species. In the Bible, a bird is an animal with wings, so bats fit that too, and a fish is an animal in the water, so whales or dolphins are fine as fish. We should therefore not imagine some kind of cynocephalic people out there that would have some genetic relation to dogs anymore more than we should think that a hippopotamus, (river horse in Greek), need have a genetic relationship with horses. Just as the ancients called those they could not understand barbarians, that is those who bark like dogs, the notion of dog-headed men appears as this encounter with a humanity which we barely see because they are too far removed from our capacity to properly see them. Moreover, just as hearing Cantonese would cause you hear chaos, it is possible to see chaos.

The notion of the cynocephalus has an important history in Christianity. It comes from the Hellenic past, from the legends of Alexander the Great and became the central image of the Christian “edge of the world”, the ultimate hostile foreigner.

I think it became important because of its strong analogies in the Bible. Christ speaks of the Canaanite woman saying, one should not give to dogs the bread that is meant for the children. And the answer of the Canaanite woman is analogous to what we see in this icon, that “even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their master’s table.”

In the icon of Pentecost we see this dog, not so much on the end of the table, but on the edge of the Church, maybe on the edge of the world. This one not a Canaanite, but a Caninite (and this symbolic slippage will cause modern interpreters to cry foul in reading the ancient accounts and say that all of this is just an error in inscription).

All these foreigners in the icon of Pentecost, culminating into the impossible monster, are the surprise we discover on the edge of the Church, anticipating maybe for the crumbs, for the antidoron maybe which we can imagine flowing out into the world so that even those who we can barely recognize as our brothers can have a foretaste of the Kingdom of Heaven.

Now the most famous cynocephalus is of course St. Christopher whose traditional icon represents him as a dog-headed warrior. There are many who have tried to say that this tradition of St. Christopher as a dog-headed man is late and is a misunderstanding of ancient texts. This is hogwash unless you think that the sixth and seventh centuries are late.

On the right is the earliest surviving image we have of St. Christopher from the six to seventh centuries, so before iconoclasm. It is a ceramic icon depicting St. Christopher next to St. George each killing snakes. Images are juxtaposed. The monster and the monster killer, two warriors facing the dragons. Also ironic is that the scholars keep telling us that the legend of St. George killing the dragon is from the twelfth century. The only evidence they allow it seems is textual despite th the existence of images that predate any textual references discovered so far.

On the right is the earliest surviving image we have of St. Christopher from the six to seventh centuries, so before iconoclasm. It is a ceramic icon depicting St. Christopher next to St. George each killing snakes. Images are juxtaposed. The monster and the monster killer, two warriors facing the dragons. Also ironic is that the scholars keep telling us that the legend of St. George killing the dragon is from the twelfth century. The only evidence they allow it seems is textual despite th the existence of images that predate any textual references discovered so far.

There was an attempt to eliminate this icon in the Russian synodal period because it did not fit modern sensibilities. I have had many people, especially priests tell me that they are bothered by this icon. I have tried to explain it and in a certain manner defend it. For example I wrote an article on St. Christopher for the Orthodox Arts Journal which is one of our most popular articles, having been viewed over 20 thousand times. When an article about a dog-headed saint is one of your most popular articles, it shows what is happening in the world.

Having said that, I would be a bit disturbed myself if one was not at least disturbed by this icon. It’s a dog-headed man after all. But isn’t that the point? I always like to say that the icon of St. Christopher is the last icon, the very edge of iconography and because it is so, it will always be ambiguous and straddle the border of what is acceptable or unacceptable in an icon.

In the Greek tradition, the icon of St. Christopher was placed above the exit door of the church, so that it would be the last thing you saw before going out into world. In the West, St. Christopher was placed on bridges, where he would represent the uneasy space of the border, the in-between and the transition.

We Need St. Christopher when the Zombies Come

I think that St. Christopher functions the patron saint of the end of the world. And although he is not my official patron, I would say that he has become so unofficially. The image below hangs in my workshop. As someone who has traveled much and lived abroad for several years, I have witnessed many miracles and have seen many signs surrounding his presence in my life.

Also, we will need St. Christopher as a guardian when the zombies come.

As we face the rising chaos, as we face the zombies, we recall the words of the Psalmist: “I am surrounded by enemies, who are like lions hungry for human flesh” (Psalm 57:4). The immediate danger is that we become afraid like St. Peter walking on the waters. There is a trope in zombie stories that says no matter how bad the onslaught of the zombies attempting to break in becomes, the true danger lies in how the human groups begin to shut themselves off completely and become pathological in their isolation. The fear of facing the possibility of the flood is to think that as in the story of Noah, the door of the Church must be closed an sealed shut.

Maybe we can get together and isolate ourselves completely. It is tempting to think so and we have heard intimations of this tendency recently. But Christ promised us that the gates of hell will not prevail on the doors of the Church. I’m not saying there isn’t a time and occasion to seal the door of the Church; we do so at least symbolically after the exit of the catechumens in the liturgy. We should and must protect our mysteries, in fact it rather seems we have often been sheepish in doing so. But I want to show you something else.

Once I encountered an image of Pentecost from a medieval Coptic church. It was the first time I saw an icon of Pentecost where the door was closed. It disturbed me profoundly to see such an image and it took some time before I understood why such an icon came into existence. And I realized or at least I speculated that the Copts had become so beset on all sides by their opponents, had been so besieged by the enemy, that it was inevitable they represent the door of Pentecost as closed. Nonetheless, to see such an image should make us weep and pray that, even as we become besieged, we find a way to keep the door of Pentecost open, for if we close those doors, we abandon the world to its continuing fragmentation.

I want to tell you a story of St. Christopher. You have all heard it, but I want to tell it maybe in a different way. The version of the story which we know best actually comes from the Western tradition. In the Western tradition, St. Christopher is not a dog-headed man, but a giant, not a Caninite but a Canaanite and in an important way, that is a descendant of Cain who is associated with the Nephilim, the giants in the Genesis flood. So although represented not as a dog-headed man but as a Canaanite, St. Christopher is still, like the Canaanite woman, that dog on the edge of the table who asks Christ for the crumbs. As hard as you try, you will not get the dog out of St. Christopher.

These are a few hybrid icons, joining the Eastern tradition with the Western one. The story of St. Christopher has him as a vicious warrior in Canaan who is looking to serve the most powerful man. He eventually finds the most renowned and powerful king until he sees that the king is afraid of the devil, and so St. Christopher goes to serve the Devil. We can see that as St. Chris toper going all the way to the end, all the way to the very extreme of what is imaginable, serving the evil one directly.

Then something happens. St. Christopher notices that the evil one is afraid of the Cross. He decides that he will serve Christ instead. Now in the story, at least the version told in the Golden Legend, St. Christopher is also a trickster and informs the king that unless the king tells him who the devil is, he will no longer serve him. But in answering St. Chris toper, this becomes the very reason why St. Christopher stops serving the king and then looks for the next most powerful one. He does the same with the devil. He tricks the devil himself in revealing Christ to him. We need to pay attention to this detail because it is an image of what St. Christopher can be for us, the key to resurrection, the double inversion which transforms the fall and death into resurrection, the trampling on death by death.

In his search for Christ, he comes to a hermit in the desert who teaches him the ways of Christianity, but when it comes to the practice, St. Christopher cannot follow the rule, he cannot follow the standard. He is a monster after all. The hermit says to fast, to abstain. St. Christopher replies he cannot. The hermit says to pray. St. Christopher replies he cannot do that either. Then the hermit says that St. Christopher should stand next to the river and help those who need to cross by hoisting them his shoulders.

Now I want you to notice how profound the story becomes here. We often think of the ark built by Noah as a holy thing and in a certain way it is. We often imagine the nave, or even the whole Church as a holy thing and in many ways it is. But in a an other, very important way, the ark is a boat full of animals. In many ways the nave is a hospital full of the sick. And so St. Christopher stands on the edge of the world, he stands on the bank of the flood. And when the Logos — the Christ Emmanuel who is the Logos implicit, the seed of God in all things — comes to the edge, it is the monster who, like an ark, carries him across.

Now I want you to think of that hermit. The hermit did not tell St. Christopher that it was fine that he could not follow the expectations of fasting and prayer. He did not say that, since St. Christopher thought it was against his nature to fast and pray, that the Church must have been wrong all along. But the hermit also did not cast St. Christopher away. He did not chase him out but rather in wisdom and economia brought St. Christoper to the edge, into the narthex on the edge of the flood where he would be the ambiguous figure that he was in the first place and eventually become a vehicle for his Lord.

A Woman in Our Parish

There is a woman named Marjolaine who comes to our parish. She has been there for years. Marjolaine is homeless and whenever she is able to find a stable place to stay, there is something in her, some thrust which makes it impossible for that stable situation to last. Generous people from the parish have tried to help her find a place, help her find stability, but there is something else going on. Marjolaine is a hermaphrodite, her appearance is confusing as she straddles the limits of what we know. Marjolaine is paranoid and possibly more. When speaking with her she jumps from one thing to the next, one subject to another, her conversation is disjointed. To speak to her is to feel she is under attack. Marjolaine comes and sits in the narthex. She usually stays there for the whole of the services. She enters the nave only rarely and then only for a few minutes.

We have invited her to come in, our priest has invited her to join us, has asked her if she wants to be catechized, if she wants to ultimately be fully received and approach communion. But Marjolaine returns to the narthex. She waits until coffee hour, eats with us and hopes that someone will give her some money before she leaves. She has memorized the services and makes little comments about some detail, some small error or confusion. She knows what is happening in the parish, the politics and the jostling that can sometimes come about, we hear strands of that. These hyper-lucid comments appear as surprises in her usual frenetic conversation.

One Sunday Marjolaine took these three small McDonald toys out of her backpack, the kind you can get in a Happy Meal, and offered them to my children. There is a tradition in Indian culture that to receive a gift from a beggar is to receive a blessing from God. And there are those who whisper that she is an angel. Once in speaking to her she told me that she also attends a mosque. A Muslim couple sometimes picks her up on Friday for prayer. Having read that last sentence, I would ask all of us to watch what happened inside us when I said that, to examine the movement of our heart when I added that last bit about the mosque. There are some of us who might be too happy that I added that, and there are those who might be too annoyed that I added that detail. She only sits in the narthex after all. There is something about the margin which always awakens our passions.

Ok, I hope I have brought many of you into a place that you are struggling to deal with, the threat of zombies, the abundance of monsters, St. Christopher, dog-headed men, people who do not fit into categories. If you feel uneasy and conflicted and a bit confused that I have moved from zombies to angels in one fell swoop, well that’s the point. This is what a fragmenting age looks like, the moment when order is not easy to inhabit because the world is filled with exceptions. Something is deeply out of place that I am here at a church conference discussing zombies but that’s where we are. Further, if we think we can deal with this age by simply shutting the door of the Church, we are going to be in serious trouble, or if we think that we can deal with this age by letting in the floodwaters then there is going to be in even more trouble.

How Do We Love Properly in an Age of Division and Chaos?

So now what do we do, how do we speak, how do we love properly in an age of division and chaos? First I think we need to look to the icon of Pentecost with humility. The chaos of the edge and the end is death, but chaos is also an opportunity for renewal and regeneration. This was true for the Sabbath and it is true in Baptism and it is true on Holy Saturday, for goodness sake it is true when we sleep. Most of us are here today because the rigid categories which legislate society are breaking down for almost three generations now. Look at us. If I were to ask everyone who is a convert to raise their hand or ask people what their ancestry is I would get a multiplicity of answers. How many are immigrants or even children of immigrants? Yet here we are in a church issued from Russia, in the southern part of the United States listening to a lecture by a French Canadian Protestant who became an Orthodox icon carver.

Our gathering serves as an image of the opportunity of Pentecost. Would this gathering have been possible even 50 years ago? Not a chance. We are here because with the breakdown of categories, things that usually would not meet can in fact meet. It is not for not an accident that Christianity increased in the twilight of the Roman Empire where the stretched multi-ethnic and multi-cultural vastness was oscillating between fragmentation, civil war and the iron fist of a Diocletian figure.

Even more telling is that our fragmentation has an unexpected side-effect. As we watch the Western world being sliced up with the increasing thin categories of identity politics like race, gender, ethnicity, age, you name it alongside the paradoxical insistence that all identities and distinctions should be dissolved, something new is emerging. People not in the church, not even in any church, are sensing that maybe Christianity was the only glue that ever held the West together no matter how precarious and volatile that unity sometimes was. The same breakdown of society that makes this meeting possible and helps some see the value of Christianity is also the breakdown which makes the zombies scratch at our door.

When the flood waters rise and monsters that inhabit the deep emerge, people look for meaning more earnestly. They are hungry for meaning. The fire of Pentecost has more room to go. For the last year or so, I have been on an adventure that came to me as a surprise. Some of you may have had inklings of this, but for very fortuitous reasons, I was pushed to start talking. As an icon carver, I had thought that my audience, those who I would be making icons or writing in the Orthodox Arts Journal for were going to be the Church or in the least the broader Christian culture. It turns out that a large part of my audience are atheists. They are recovering atheists, agnostics, honest atheists who ask the hard questions and desire understanding because they are seeing things collapse. They see the hemorrhaging of our culture and want to understand how to stop the bleeding.

I get letter after letter (for a long period of time I get a message everyday) from people who are looking for meaning, people who are moving away from their criticism of the 13 year old’s understanding of Christ, and discovering the cosmic vision of Christ who hangs in the dome above the world, and the cosmic vision of his mother who’s womb is wider than the heavens. There is so much to say to such people. We hold in our hearts the tradition of Christ, which connects through a beautiful braid of analogies in the personal, the social, the cosmic and the transcendent realms.

Of all Christians, the Orthodox do not see the stories of the Bible, the story of salvation as just an arbitrary set of facts one must believe in to be saved. Of all Christians, the Orthodox know that the organic process of salvation, the transformation of man into god through participation in the life of God, is the very manner by which the world exists, is the very thing that links outward phenomena to consciousness, to nous, to logos and unites all things in love towards the infinite. How awesome is that?

And in the background we have also kept and hold the keys not only to Christianity, but we also hold the heritage of the ancients. We are not Platonists but we hold to the heritage of Plato. We are not Aristotelian but we hold to the heritage of Aristotle. We hold to the heritage of Alexander, Homer, Virgil and others. We add to them the useful stories of all people who enter into communion with Christ as well. We keep them alive in the narthex of the Church so that we can participate in the manner to which we can in the divine life. We hold the golden thread that reaches back into the mists of time, that same golden thread that is under increasing threat of being cut.

And so the chaos is a test much like the waters of Baptism that washes off all that which is superficial, all that which we hold but have not integrated. Encountering the outer darkness, being challenged by the outer chaos is an urgent test for Christians to know in our hearts and minds to the extent that it is possible what exactly is this thing we call the incarnation really is and how it anchors the world.

This is a mystery but we need to know why mystery matters. We need articulate why some things cannot be described or contained and why that mystery is nevertheless the fount of existence. Our feebleness to understand and to live in Christ is and will increasingly become an opportunity to be mocked — sometimes with reason. Our hypocrisy and our pride, our smugness and our incapacity to hear the world, even the cry of the zombies as they scream their desire for meaning, will be our downfall if we don’t listen or respond.

I think that the answer bout how to engage the fragmenting world lies in the story of St. Christopher. As we travel further away from the altar we must never compromise its purity but as we move to the nave and to through the narthex, as we move out in a candle-lit procession out into the world, our compassion must grow as Christ’s compassion grew when faced with the adulterous woman, the rich thieving tax collector, the heretical Samaritan woman. We can do this without compromising the purity of the altar or the rigor of the sacramental life. Christ protected the purity of the holy place, cleared the temple of lies and corruption. Christ can both hold a whip in his left hand while blessing with his right hand.

We should not confuse the altar with the narthex. In fact we offer the very structure of the church itself as a ladder whose first bar is plunged unapologetically into the mud, planted maybe in the very belly of hell but nonetheless reaches all the way to the heaven into the throne room of God.

As we preserve the hierarchy of salvation however, take heed to a warning. We must remain humble enough to notice the holy fool in the chaos, the exception who reminds us that the hierarchy is for us and not for God who is beyond all distinction. We need the humility to perceive that sometimes, by the grace of our Lord, the Monster on the edge of world will be the person by which Christ is carried further out into the world than what we ever thought possible.

About the Author

-

Jonathan Pageau graduated with distinction from the Painting and Drawing program at Concordia University in Montreal during the late 1990s. Quickly disillusioned with contemporary art, he discovered icons and traditional Christian images along his own spiritual journey. Having studied Orthodox Theology and Iconology at the University of Sherbrooke, since 2003 Jonathan has been carving different types of liturgical objects. His carvings have been commissioned by churches, bishops, priests and laypeople in the United States, Canada, Europe and Asia.

Jonathan has participated is several exhibitions of icons and teaches icon carving with Hexamaeron. Vist his website Pageau Carvings. Read his articles on the Orthodox Arts Journal website.

- April 18, 2018ArticlesZombies, Monsters and a Dog-Headed Saint