The author of this essay, Andrei Manovtsev, is one of the foremost scholars of the lives of the Tsar Nicholas II and his family. He has contributed greatly to the current research on what are for now being called the “Ekaterinburg remains”—bone fragments unearthed near Ekaterinburg that are believed by some to belong to the Royal Family.

In this review of a book by Konstantin Kapkov that is written in Russian and not yet translated into English, Manostev gives us a glimpse of the Royal Family’s hidden inner world.

Source: Orthodox Christianity

By Andrei Manovtsev

A Brief Overview

The book’s title may seem surprising at first glance. Can we really define one’s spiritual world? And especially the spiritual world of a man and his family? For the Orthodox Christian, everything becomes clear very soon. Kapkov’s book simply describes the Royal Family as a family living within the Church, a religious family. Having read the book, one becomes certain that the words from the Troparion for the Royal Passion-bearers, naming the family “the only home church of Christ”, are absolutely true. We will try to speak about this in our review.

A man’s spiritual world certainly beggars any description. A secular person might define this notion as one’s good education, erudition, love for music, and culture in general. For a religious person, however, the Church’s expression, “spiritual world”, envisages, first of all, a reverent attitude towards this world, and therefore, a tactful distance, rather than interest. We do not see anything excessive in the book by Konstantin Kapkov, there is nothing that would seem “indelicate”. It is a story telling us how they attended church and observed fasts, how often they received the Holy Mysteries, and which church they attended in particular—it mostly consists of dry enumerations. Thus, the book must seem tiresome for a person living outside the Church. But for a believer, the book is a description of such precious things that the “dry” facts will in no way appear dry. A believer knows it is difficult, in fact impossible to speak about the treasure hidden behind these facts. Through the “dry” facts, one can see that the unutterable, the sanctity that can only be acquired within the Church was of the same value and significance for the royal family.

It is worth stressing that the Royal Family’s involvement in Church life was not just a matter of esthetics, but natural. In the church their living hearts met the Living Christ. Their life in Christ in the world and observation of the commandment of love are the best testimony. Kapkov’s book fully illustrates this. It is also important that the author managed to show—mainly through the extracts preserved from Empress’s and her daughters’ journals—that their self-giving love was a fruit of the word sewn in their hearts, the word of the Gospel and of the saints. Here we see Christ’s Parable of the Sower coming true: But that on the good ground are they, which in an honest and good heart, having heard the word, keep it, and bring forth fruit with patience (Luke 8, 15). We do not think about what it cost the royal family to bear the royal cross. Konstantin Kapkov pays heed to the crucial word. We learn that at the very beginning of their path together, the Tsar told his spouse that their principal motto should be: patience.

The life of the Tsar Martyr and his personality are veiled in real secrets but also in various legendary and mystical ideas. The book covers some popular beliefs and dispels them in a positive, unbiased and conscious way.

The history of the twentieth century contains a key event: the dethronement of Tsar Nicholas II. The author conclusively proves this was not an abdication, but a dethronement.

Speaking about their period of confinement, Konstantin Kapkov shows the reader what difficulties—concerning their church life—the royal family had to encounter. The author is rather critical of the clergy, but manages to remain unbiased (which is characteristic of him).

Finally, one section of the book is devoted to an issue that is not of a spiritual naturethis is the Empress’s health; but even here the author speaks constructively, to the point. Many people (amongst whom are also Orthodox Christians) are still convinced that Empress Alexandra Feodorovna is to blame for all the troubles Russia suffered in the twentieth century. This conviction is sometimes so firm that it is no use trying to talk anyone around it, they will not hear it anyway. In fact, nothing was so destructive for Russia as the slander against the Tsarinaand that slander was malicious. The people did not see “a living person” in Alexandra Feodorovna, they only wanted her to comply with what she was expected to be. The Empress’ notorious secular failures can mainly be accounted for her poor health, therefore, thanks to Konstantin Kapkov, we begin to see the situation from the inside. It was a real discovery of Kapkov to compare (using various documents, letters, diaries) words of Alexandra Feodorovna about spirituality in her youth and middle age. Her attitude in both stages of life are surprisingly similar! Thus, we can see her personal integrity.

To give the reader a better understanding of the book, we offer a review in the style of a digest, talking about the Royal Family’s Church life. The numbers in brackets stand for the page in the book. The dates correspond to the Old Style, as they do in the book.

Numbers and Facts as Testimonies to the Faith

The first chapter of the book by Konstantin Kapkov is called The Royal Family’s Discipline of Prayer, Fasting and Eucharistic Life. The expression, “Church discipline”, doesn’t sound bureaucratic for those who regularly go to church, confession and receive communion. Moreover, this expression was natural for Tsar Nicholas II, who was always sober and self-disciplined in everything.

The Tsar missed Sunday Liturgies extremely rarely and only when it was strictly necessary. He almost always attended church on great feast days. Konstantin Kapkov shows how many times—over the twenty-three years of his reign—the Emperor attended the service on each feast day. He never missed any service on Pascha or the Nativity of Christ, and the same applies to some other feasts. On the average, in each of his twenty-three years on the throne, the Tsar attended the church services on fifteen Great Feasts.

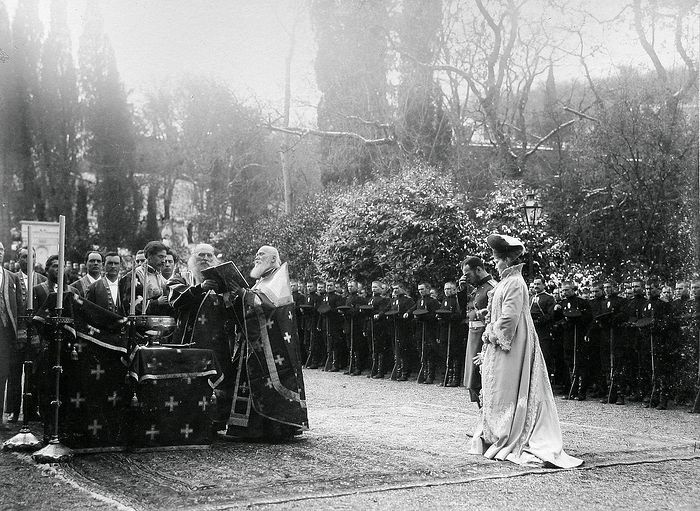

Besides the Great Feasts and Sunday Liturgies, Nicholas II often went to various church feasts, jubilees and celebrations. He was usually with his wife. On such occasions, a paraclesis would normally be served. We need only look at the photos below to be convinced that for the Royal Passion-bearers, attending services was not tedious standing motivated by mere necessity.

Here it is worth mentioning that the book contains an abundance of photos; though small in size, they are good quality photos provided with informative comments written by the author.

It is a well-known fact that the Church tradition of participating in the Church’s key sacrament, the Eucharist, considerably changed in twentieth century as compared to the nineteenth century. In the nineteenth century it was customary for Russian Orthodox Christians to approach the chalice once a year, usually during Great Lent. Kapkov clarifies how often and on what occasions members of the Royal Family received Communion. They communed two times a year, during the first week of Great Lent and on Great Thursday. One more day became customary in 1909. This was October 21, the day Nicholas II ascended the throne. The children received Communion more often, both on their birthdays and name days. Tsarevich Alexei communed on days of illness. There were additionally three special days when the Emperor received Communion: May 14, 1896, during the rite of Sacred Coronation; June 18, 1903, on the eve of the glorification of St. Seraphim of Sarov, and on August 9, 1915. About the last date Kapkov writes, “Probably, it was in order to pray for the health of Tsarevich”, as the Church commemorates the Martyr Alexius on this day. However, St. Alexius of Moscow was the Tsarevich’s patron saint ,not the Martyr Alexius. It is more probable that Tsar received Communion on August 9, 1915, before he was to assume the role of commander of the Russian Army. We can show it was highly likely that the Emperor made the decision on August 10, 1915. Thus, it is possible that the Tsar’s intention became firm on August 9, after the Communion.

In the book, citations from his personal diaries mark the Tsar’s reverential attitude toward the sacrament of the Eucharist. For example, “I was vouchsafed to receive the Holy Mysteries. A great and grace-filled moment” (34).

“As a woman, the Empress linked the joy of Communion with the hope of becoming closer to her husband and a wish to be useful to him,” the author says, illustrating these words with excerpts from her letters. Here is an example: “Oh, dear, what a consolation it is to take Communion together in this time of troubles. May Holy Communion strengthen you, make your will firm to fulfill the severe destiny the Lord has placed upon you. If there is something I can assist you in, I can only pray with all my heart and soul for you and for our beloved country” (45). The Empress expressed her maternal care for her servants through her wish to make sure that they were also close to Christ. The author tells us the following: “Meeting with the afflicted, the Empress was trying to convince them that in bad times it was important to receive Christ. She shared this view with her husband when the First World War began: ‘How significant it is to have a chance to receive Communion at such moments of sorrow, and how much I want to help others to remember that God granted this blessing to everyone; Communion is not something obligatory, something we must receive once a year during Lent. He gave this to us to take when our soul is longing for it and needs strength…’” (45). We know precedents when these conversations with Alexandra Feodorovna produced a very positive effect on the wounded, and afterward they would finally agree to take communion.

Any Orthodox woman could share the happiness of Alexandra Feodorovna in her narration of how Tsarevich Alexei received Communion in Spala in 1912; the boy was severely ill then. “His poor gaunt face with large suffering eyes suddenly radiated with grace-filled joy when the priest came up to him with the Holy Gifts. This was such a comfort for us, and we felt the same delight.” (43)

With regard to fasting, Konstantin Kapkov notes, “The discipline of fasting in the royal family was not complicated at all” (31), and talks about the features of this discipline. Telling us about the Passion-bearers’ sincere view of Confession, the author points out that this was unusual for those in power as their contacts with a priest were often formal. “The priests often lacked courage, they were afraid to hear their confessions, while the rich man would not find it necessary to condescend to a priest. The latter simply covered the head of the “repentant” with his epitrachelion and read the prayer of absolution” (37).

Concluding Chapter 1, Kapkov says, “Thus, we see that the royal family was very religious. Emperor Nicholas II was a monarch living within the Church; he loved Orthodox rites, traditions, and prayers. The discipline of fasting in the Emperor’s family was not complicated at all. Tsar Nicholas II received the Holy Mysteries of Christ on almost a set number of feasts, except for special occasions. This order testifies to a measured, stable spiritual life” (46).

A topic that runs throughout Kapkov’s reflections and narration about the Royal Passion-bearers is the simplicity and modesty that they manifested in everything, even in their attitude towards icons. The author describes the multitude of icons left in the Ipatiev House (the valuable ones were stolen), in the chapter named Spiritual Formation of the Sovereigns. Kapkov finishes his description, “All the above-mentioned images were of various sizes, made on various materials: on wood, plaster, enamel, or tinplate. All the icons (except for a little image of St. George the Victory-bearer) were very plain; images of this kind are printed in numerous copies and do not have any additional decorations or ornaments they are something anyone can afford” (116) (emphasis by the author.—A.M). Nearly every icon had an inscription on the reverse side, which was always the date when the icon had been bought or presented. For instance, “Our Lady of the Sign” and the inscription: “A blessing to our dear Olga. Father and mother. Spala. November 3, 1912.” Another example, “Blessed Heaven. From Anya, 1916.”

Their view of the church was just as simple, but we should note their exquisite taste. Concerning the various churches linked to the royal family, the author concludes, “The most eminent architects of Russia and Europe worked on the churches, but all the projects were supervised and agreed to personally by either the Emperor, or the Empress (in cases were the church was being built under her patronage), who went into each detail. Looking at the plans or buildings that have been preserved, we can see that the royal couple had impeccable artistic taste, and we can say, a spiritual understanding of art; although, personally, they preferred to pray in small, even mobile churches, as well as underground [cave] churches” (73-74).

One of the many impressive citations provided by the author tells us about the Empress in church. This is the reminiscence of General A. Molosov: “I often chanced to see the Empress during church services. She usually stood without the slightest movement, and looking at her countenance, one could see she was praying” (83).

Much evidence (primarily in the Empress’ letters) has come down to us revealing how important prayer was for the family. Their prayerful life, however, also had its order, just as everything else: They had morning and evening prayers, and the family never began to eat without praying. The book certainly reflects this information.

On the Need for a New Edition

The book written by Konstantin Kapkov is a compendium of unique historical research that defuses rumors of the royal couple’s so-called lack of spiritual health. It gives us a chance to imagine how the Sovereigns managed to bear their cross—they derived strength from above—typical of an ordinary religious Orthodox Christian. We assume the author could have paid more attention to this subject the bearing of the cross. We also think he could—at least partially—shift the balance of attention favoring the Empress (due to the fact there were more documents preserved about her). The distribution of topics and highlights, as well as some other moments, may be altered in favor of greater constructiveness and wholeness of research. To sum up, I wish the author a fruitful work on a new edition of his wonderful book.

About the Author

- Andrei Manovtsev, is one of the foremost scholars of the lives of the Tsar Nicholas II and his family. He has contributed greatly to the current research on what are for now being called the "Ekaterinburg remains" -- bone fragments unearthed near Ekaterinburg that are believed by some to belong to the Royal Family.