Fr. Stephen Siniari

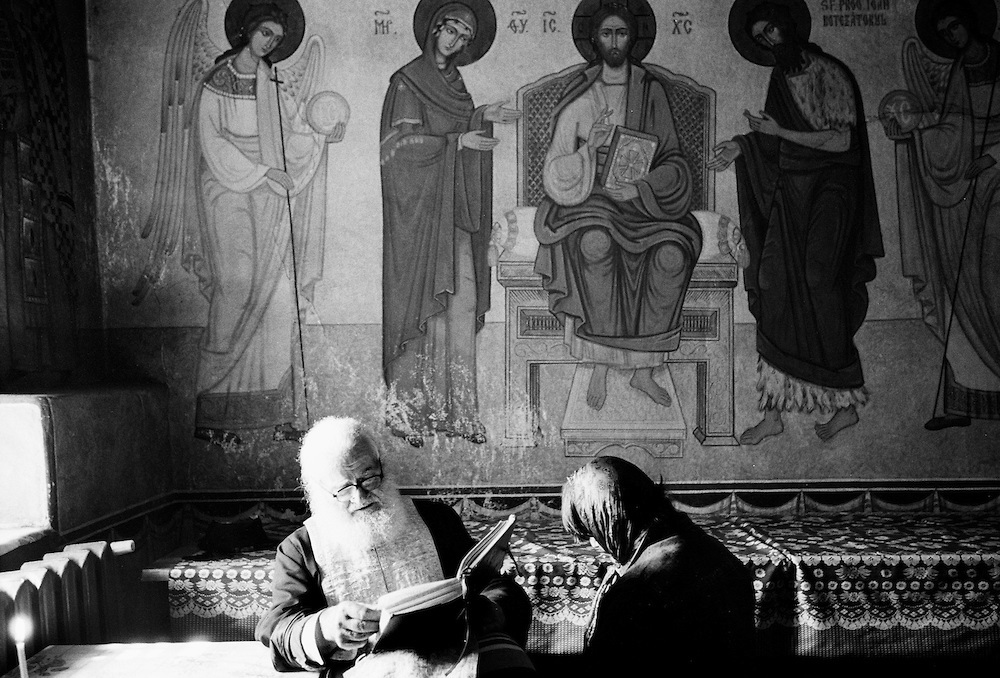

A man came to the parish. He remained in the back. Candles were burning. Vesperal prayers were rising with the incense. People had baked the Holy Bread. Three loaves were sitting on a table near the iconostasis in the front. The faithful were following the priest, making the Trisagion prostrations and kneeling for the Lord’s Prayer. Together they sang, “O Gladsome Light.” Together they prayed, “Vouchsafe, O Lord, to keep us this night without sin. Blessed art Thou, O Lord, God of our fathers…”

The man came back again. He wanted to know more about what seemed new and true and exciting to him, but very hard to understand conceptually. He learned that the Apostles had visited the ancestral villages of these very people and taught them many things. He learned that they had customs and practices that had been passed down generation to generation. He knew they also had a book. A special book that told about the early history of their community.

The man had long possessed a great sensitivity to the brevity of life. He held a great hope that there must be more, beyond this life, and he longed to know if there was some way to prepare for it. He wanted answers and sensed that he might find them here. Once he sat together with the priest in the darkened church for a long time. As they spoke, he began writing his thoughts on a small piece of paper.

The people and the priest were kind in their responses to his questions. But at the same time, they didn’t seem overly concerned with precise and definitive resolutions.

The priest said strange things, things like, it’s always ontology over theology. Relationship over rubric. Experience over explanation, and love over logic.

For the man, it was frustrating. Once he even announced that he needed to know the formal theology of the church. But instead of telling him which volumes might contain these certain and universally valid truths, he was told that the devil is a better theologian than any of us, but he remains the devil.

Wanting to help, the priest suggested that the process of coming to know God was not an intellectual endeavor at all and that it would probably take time. And if we do read texts, the Fathers say we should read not for knowledge, but for salvation.

Collect concrete, living insights and understanding, the priest suggested, as best you can, drawn upon your vital experience with God and not from books. Read, pray, give to the poor, do labor on behalf of someone who cannot do it, all in secret, if possible. And fast, doing this while keeping in mind that periodically refraining from food, drink, and sexual activity for married folks, is only one means of fasting. Words, thoughts, entertainments, and, pretending to serve as General Manager of the Universe—we would do well to cut back in those areas too.

Of all these things, fasting seemed the most puzzling, perhaps because it seemed to have so little connection with morality, with being good and righteous, and he had always heard that religion was about being moral and good. But at the same time, this had always given him a certain disdain for Christianity, which seemed quite unnecessary as an aid to being good and upright (we all have our own “virtuous atheists’ to exhibit). To the contrary, the priest told him that fasting was not about being “a good person” at all. Rather, it was an ascetic practice, exercising certain important spiritual muscles. It was not about being moral, but about being holy, about becoming (and this seemed so audacious at first) friends with God.

Wait until tomorrow, he told the man, and we’ll discuss it with the whole parish, with the people who have maintained these ancient traditions for so many years, often in the throes of hardship, dispersal, and persecution. People for whom fasting still flows in their veins. For this, he told the man, is the kind of understanding that will get you somewhere.

So when it was time for the sermon, the priest announced that there would instead be a contest. They would compete with one another in answering a quiz, a True/False exam, with the men against the women. After telling everyone in advance, with a wink, that all the answers are false, the priest began, ladies first.

We fast to repudiate food, sex, and drink, as evil. True or False?

False, a young woman, feeding her cooing two year old, answered with a bemused expression. If we condemn those things as evil, the priest added, we condemn their author, who is God Himself. And more than a few listeners were taken aback to hear that certain canons of the Church anathematize anyone who would refrain from meat, wine, or sex not for ascetic reasons, but because they found them disgusting or unclean, for such people unthinkingly blaspheme against the goodness of God’s creation.

We fast to please God. True or False?

One of the men, a former Naval Officer, knew the workings and rewards of true obedience and discipline. False, he said. The priest nodded approvingly, and pointed out that the devil never eats. Certainly he does not please God.

We fast to punish ourselves. True or False?

The parishioners were getting warmed up now. Knowing from several of her friends about certain religions where people intentionally inflict bodily injury and suffering upon themselves as a form of supposed piety, and knowing that her precious Orthodox faith had never taught her any of these appalling attitudes, one of the woman answered firmly, False. God takes no pleasure in our suffering.

The priest smiled, and the women were ahead, two to one.

We fast as a reparation for sin. True or False?

The big man who had all the keys to the church, and whose family still lived near the Mount of Olives in the old country answered, False.

With an inspired eloquence that surprised everyone, he explained: the only reparation for sin, for falling short, for our separation from God, His creation, and our fellow man—for what Father Abraham described as a great chasm separating us from life—the only reparation we have ever known is our Master Jesus Christ, the Way, and the Truth, and the Life.

The contest now stood as a tie, between the men and the women.

So then, the priest went on, it must be that we fast as a sacrifice to God for our sins. We give stuff up, as a sacrifice for our sins. True or False?

There was some hesitation. But before too long, the grandmother in the hat, the one who had taught the priest as a young boy, looked him squarely in the eye. “False,” she said with conviction.

As if to rival the oratory of the stout man who had just spoken, she went on:

The priest has taught us more than once that among the early Christians, and still in Orthodox lands today, fasting was an ascetical effort of the entire community, not an individual trial designed so we could add our sacrificial contribution to Christ’s sacrifice because of personal debt incurred by our sins.

On the Cross, Christ Jesus offers for all time, a single sacrifice for sins. Abraham prepared to offer his son Isaac. But God provided His own sacrifice bonding the relationship of the Old Covenant and provides the only sacrifice efficacious for overcoming sin, by the blood of our Lord Jesus Christ in the Eucharistic Community of the New Covenant.

The women were ahead, three to two.

Finally, we fast to make ourselves worthy to receive Holy Communion. True or False?

This was hard, even for us who know the answer beforehand, for after all we really are supposed to fast before Holy Communion. The big man with all the keys later said he sensed a trick question and immediately blurted out, True, preventing anyone else from answering. And that’s how the ladies won.

Knowing how seriously he himself prepared for Communion: reflection, prayer, fasting, reading, reconciliation, helping others, and Holy Confession, the people were pretty sure he did it on purpose, knew just what he was doing. He responded afterwards with an ambiguous grin, “Who knows? God knows.”

When the suspense of the contest had quieted down a bit, the outcome now assured, the priest allowed a holy silence to prevail for long enough to arouse some discomfort. Then he spoke: “The transfiguration of creation and of man in liturgical space and time… the contraction of past and future into the present moment of participation in God’s Glory… the inseparable gathering of the faithful… the personal union of created and uncreated, in the Body and Blood of Christ…”

Whatever the ascetic blessings of fasting, the holy mysteries must always be received, not taken—received as a gift and never earned as something we deserve. The fathers say we can fast to the edge of our endurance, while at the same time hanging from ceiling hooks by our nostrils, and still never be worthy of the gift of Jesus Christ in the Holy Communion of His Church, “God’s continuing entry into the world.”

The man with so many questions looked at his jottings in the little notepad he now kept in his pocket when he came to Church. He realized that he had taken only very short, faltering steps, not always just right, but the contest had helped him see that overall they seemed like steps in the right direction.

Then he could not help asking one last thing, and his voice rang out as clear as a bell: then why, after all this is said and done, why do we fast?

The priest lifted up his palms in mock despair. But he grinned indulgently, and said:

It’s really simple.

We fast because Jesus fasted and because He taught his disciples to fast.

Simple.

All Orthodox theology begins and ends with Jesus Christ.

But the man still seemed disappointed, even though the parishioners thought this to be a very fine answer. So as a last concession, and out of compassion for the stranger who wanted to learn, the priest talked about a very old Greek word that had come to play an important role in the lexicon of the Church. Yet he didn’t start with the word at all, but with the false reality from which the man had himself hoped to find a refuge, the reality to which the word itself suggested an antidote:

In the American society that surrounds us, the Church seems everywhere to be in decline, losing participants, losing popularity, losing ground. And in response, some misguided leaders have tried to make Christianity into something easy and popular and accessible, proclaiming that it’s really only about being a good person (“Just go out and be nice,” as the man had actually heard one Mainline Protestant minister exhort to his flock) and along the way enjoying the favors of a deity who only wants us to be happy.

But this is not the real thing at all, as our people here all know quite well. Christianity is not easy but hard. Real Christianity is about attempting difficult, even impossible things, things that are conceivable only through the hope of divine aid to accomplish them. Things like being able to experience the divine energies .themselves—perhaps only now and then in a sparkling, mystical moment—even becoming one with them. Things like giving up everything you think you have, if not sooner, then later at the hour of our death, to enter a land that seems strange and frightening and wonderful, walking on the holy ground that forced Moses to remove his sandals before a Fire that made him look away, lest he be blinded. Arriving at another land that we will discover is in fact our native land, where our true names and our true faces will be revealed, and where all the rules and all the possessions of this alien land will be superseded. And we had better prepare for all this. We need to train. Subject ourselves to rigorous discipline.

The Greek athletes, the original Olympians, called this training “askesis.” For us, fasting is a privileged mode of spiritual training, lending us the athleticism of the soul that will make such astonishing feats of the spirit conceivable and even plausible, given the abundant race of our merciful God. By ascetically taming the demands of the stomach, it subdues all the other passions, and allows a quietude and peace and stillness within which we can hear the “still small voice” of God, the voice that we can still hear “after the earthquake” and “after the fire” (1Kings 19:11-13). That’s why all the holy figures of the Church (think of St Elias, of St John the Forerunner, of our Lord Himself) have all been great fasters.

But we should also recall the words of the Russian theologian Khomiakov: “We know that when any one of us falls, he falls alone; but no one is saved alone.” That is, individual ascetic effort, undertaken in isolation, may actually skew our vision, leading us to believe that we are saved by our own efforts. Rather, it is through our common effort during times of fasting, together with the shared experience of the saints, that the Church transfigures individual ascetic struggle, as we participate in the salvation accomplished in the Body of Christ, our Master who fasted and who said, the time will come when my disciples will fast.

But we should also recall the words of the Russian theologian Khomiakov: “We know that when any one of us falls, he falls alone; but no one is saved alone.” That is, individual ascetic effort, undertaken in isolation, may actually skew our vision, leading us to believe that we are saved by our own efforts. Rather, it is through our common effort during times of fasting, together with the shared experience of the saints, that the Church transfigures individual ascetic struggle, as we participate in the salvation accomplished in the Body of Christ, our Master who fasted and who said, the time will come when my disciples will fast.

Finally, in fasting as in all other ascetic endeavors, and as the first rule of the Unseen Warfare reminds us, never believe in oneself, nor trust oneself in anything. So, don't self-diagnose and don’t self-prescribe. We do not, for example, decide on our own what we will give up for Lent. Serious pilgrims intent on the Kingdom of Pascha always have a guide. St. Basil the Great says, "It is unhealthy to live in a situation without a brother to rebuke you." To be sure, the standard is the same for all, but we're not all at the same place along the journey. Our confessor knows our particular strengths and weakness and will recommend the prescription that will allow for continued growth in our Master Christ, by the love of the Father, through the grace of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

So as it turned out, the priest gave a sermon after all.

And through the spirited struggle of the contest, not only did the man who was no longer a stranger get a glimpse of what he had been seeking all along, but also for at least a time, he finally understood what would be required of him in order to really understand.

About the Author

-

Father Stephen N. Siniari is a priest of the OCA Diocese of the South. During more than 30 years as a priest, Father Stephen served parishes in New England and the Philadelphia/South Jersey area while working full-time for an international agency as a Street Outreach worker serving homeless, at-risk, and trafficked teens. He currently lives on the Florida Gulf Coast with is wife of more than 40 years.

He is the author a three-part series of stories, featuring the fictional Father Naum, long-time priest at Saint Alexander the Whirling Dervish Parish in the ethnically diverse Philadelphia neighborhood of Fishtown. The first volume, Big in Heaven: Orthodox Christian Short Stories, is forthcoming from Ancient Faith Publishing.

- January 13, 2020ArticlesThe Death of the Lion and the Dream of the Jersey Shore: Maturity Seasoned In Time

- October 26, 2019ArticlesThe Bishop — A Short Story by Fr. Stephen Siniari

- July 25, 2019ArticlesMarriage: Instructions from a Manual That Does Not Yet Exist

- April 1, 2019ArticlesAn Independent Operator