In this recollection of his youth, the noted English writer G. K. Chesterton reflects on the terrifying and lingering impact of an encounter with evil in the person of one of his companions. The narrative is made unusually powerful by the skill with which Chesterton reveals the invisible concealed within the visible, the supernatural cloaked within the natural and mundane, deep metaphysical realities emerging from within what could easily be taken as a banal and everyday encounter. Along the way, he dramatizes the ancient insight (forming the great, underlying claim of Plato’s “Republic”) that evil corrodes and ultimately devastates the soul of the evildoer himself.

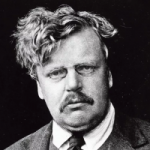

By G.K. Chesterton

What I have now to relate really happened; yet there was no element in it of practical politics or of personal danger. It was simply a quiet conversation which I had with another man. But that quiet conversation was by far the most terrible thing that has ever happened to me in my life. It happened so long ago that I cannot be certain of the exact words of the dialogue, only of its main questions and answers; but there is one sentence in it for which I can answer absolutely and word for word. It was a sentence so awful that I could not forget it if I would. It was the last sentence spoken; and it was not spoken to me.

* * *

The thing befell me in the days when I was at an art school. An art school is different from almost all other schools or colleges in this respect: that, being of new and crude creation and of lax discipline, it presents a specially strong contrast between the industrious and the idle. People at an art school either do an atrocious amount of work or do no work at all. I belonged, along with other charming people, to the latter class; and this threw me often into the society of men who were very different from myself, and who were idle for reasons very different from mine. I was idle because I was very much occupied; I was engaged about that time in discovering, to my own extreme and lasting astonishment, that I was not an atheist. But there were others also at loose ends who were engaged in discovering what Carlyle called (I think with needless delicacy) the fact that ginger is hot in the mouth.

I value that time, in short, because it made me acquainted with a good representative number of blackguards.2

It was just such a man whom I came to know well. It was strange, perhaps, that he liked his dirty, drunken society; it was stranger still, perhaps, that he liked my society. For hours of the day he would talk with me about Milton or Gothic architecture; for hours of the night he would go where I have no wish to follow him, even in speculation. He was a man with a long, ironical face, and close and red hair; he was by class a gentleman, and could walk like one, but preferred, for some reason, to walk like a groom carrying two pails. He looked liked a sort of Super-jockey; as if some archangel had gone on the Turf. And I shall never forget the half-hour in which he and I argued about real things for the first and the last time.

* * *

Along the front of the big building of which our school was a part ran a huge slope of stone steps, higher, I think, than those that lead up to St. Paul’s Cathedral. On a black wintry evening he and I were wandering on these cold heights, which seemed as dreary as a pyramid under the stars. The one thing visible below us in the blackness was a burning and blowing fire; for some gardener (I suppose) was burning something in the grounds, and from time to time the red sparks went whirling past us like a swarm of scarlet insects in the dark. Above us also it was gloom; but if one stared long enough at that upper darkness, one saw vertical stripes of grey in the black and then became conscious of the colossal facade of the Doric building, phantasmal, yet filling the sky, as if Heaven were still filled with the gigantic ghost of Paganism.

* * *

The man asked me abruptly why I was becoming orthodox.3 Until he said it, I really had not known that I was; but the moment he had said it I knew it to be literally true. And the process had been so long and full that I answered him at once out of existing stores of explanation.

“I am becoming orthodox,” I said, “because I have come, rightly or wrongly, after stretching my brain till it bursts, to the old belief that heresy is worse even than sin. An error is more menacing than a crime, for an error begets crimes. An Imperialist is worse than a pirate. For an Imperialist keeps a school for pirates; he teaches piracy disinterestedly and without an adequate salary. A Free Lover is worse than a profligate. For a profligate is serious and reckless even in his shortest love; while a Free Lover is cautious and irresponsible even in his longest devotion. I hate modern doubt because it is dangerous.”

“You mean dangerous to morality,” he said in a voice of wonderful gentleness. “I expect you are right. But why do you care about morality?”

I glanced at his face quickly. He had thrust out his neck as he had a trick of doing; and so brought his face abruptly into the light of the bonfire from below, like a face in the footlights. His long chin and high cheek-bones were lit up infernally from underneath; so that he looked like a fiend staring down into the flaming pit. I had an unmeaning sense of being tempted in a wilderness; and even as I paused a burst of red sparks broke past.

“Aren’t those sparks splendid?” I said.

“Yes,” he replied.

“That is all that I ask you to admit,” said I. “Give me those few red specks and I will deduce Christian morality. Once I thought like you, that one’s pleasure in a flying spark was a thing that could come and go with that spark. Once I thought that the delight was as free as the fire. Once I thought that red star we see was alone in space. But now I know that the red star is only on the apex of an invisible pyramid of virtues. That red fire is only the flower on a stalk of living habits, which you cannot see. Only because your mother made you say ‘Thank you’ for a bun are you now able to thank Nature or chaos for those red stars of an instant or for the white stars of all time.4 Only because you were humble before fireworks on the fifth of November do you now enjoy any fireworks that you chance to see.5 You only like them being red because you were told about the blood of the martyrs; you only like them being bright because brightness is a glory. That flame flowered out of virtues, and it will fade with virtues. Seduce a woman, and that spark will be less bright. Shed blood, and that spark will be less red. Be really bad, and they will be to you like the spots on a wall-paper.”

He had a horrible fairness of the intellect that made me despair of his soul. A common, harmless atheist would have denied that religion produced humility or humility a simple joy: but he admitted both. He only said, “But shall I not find in evil a life of its own? Granted that for every woman I ruin one of those red sparks will go out: will not the expanding pleasure of ruin . . .”

“Do you see that fire?” I asked. “If we had a real fighting democracy, some one would burn you in it; like the devil-worshipper that you are.”

“Perhaps,” he said, in his tired, fair way. “Only what you call evil I call good.”

He went down the great steps alone, and I felt as if I wanted the steps swept and cleaned. I followed later, and as I went to find my hat in the low, dark passage where it hung, I suddenly heard his voice again, but the words were inaudible. I stopped, startled: then I heard the voice of one of the vilest of his associates saying, “Nobody can possibly know.” And then I heard those two or three words which I remember in every syllable and cannot forget. I heard the Diabolist say, “I tell you I have done everything else. If I do that I shan’t know the difference between right and wrong.” I rushed out without daring to pause; and as I passed the fire I did not know whether it was hell or the furious love of God.

I have since heard that he died: it may be said, I think, that he committed suicide; though he did it with tools of pleasure, not with tools of pain. God help him, I know the road he went; but I have never known, or even dared to think, what was that place at which he stopped and refrained.

(Chapter XXXIV of Tremendous Trifles, 1909)

FOOTNOTES

- Chesterton’s original title is simply “The Diabolist.” The old word “diabolist,” from the Greek diabolos or [the] devil, refers to someone who has dealings with the devil, or more generally a devil-worshipper.

- “Blackguard” is an old English term for someone who today would more likely be called a “scoundrel.”

- Chesterton, a Roman Catholic convert, is of course referring only to “orthodox Christianity” in a generic sense.

- Chesterton’s English usage here probably refers to the “bun” that is, according to the OED, “a small round sweet bread or cake with currants, etc.”

- On November 5 England celebrates Guy Fawkes Night, also known as Bonfire Night and Fireworks Night.

About the Author

-

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936), was an English writer, poet, philosopher, dramatist, journalist, orator, lay theologian, biographer, and literary and art critic. Chesterton is often referred to as the "prince of paradox."

Chesterton is well known for his fictional priest-detective Father Brown, and for his reasoned apologetics. Even some of those who disagree with him have recognised the wide appeal of such works as "Orthodoxy" and "The Everlasting Man." Chesterton routinely referred to himself as an "orthodox" Christian, and came to identify this position more and more with Catholicism, eventually converting to Catholicism from High Church Anglicanism.