By Mary Lowell

Source: Orthodox Arts Journal.

Professor John Yiannias, Ph.D., expert in Early Christian and Byzantine Art, University of Pittsburgh, has a bold opinion on the issue of why “write” is the wrong verb to use for making an icon.

“While, on the face of it, the subject may appear only tangentially relevant to American Orthodox history, it is actually rather relevant, in that the term “icon writing” is peculiar to American (or, at least, English-speaking) Orthodoxy, and may very likely have originated here in North America.”1

In his August 3, 2011 post Is an Icon Painted or “Written?”, blogger David also disparages the use of the English verb in all its conjugations (write, writing, written).

That may seem an odd question, because as any sensible person can see, icons are painted; they are paint applied to a surface of some kind. Why, then, does such a question even arise? The answer lies in the usage by many English-speaking neo-Eastern Orthodox of a kind of affected jargon in referring to icons. They will say one ‘writes’ an icon rather than ‘paints’ it. But the reason for that peculiar usage lies in the differences between the English and the Russian languages.2

Yiannias speculates that the phrase “icon writing” may be a North American invention and Blogger David calls it “neo-Eastern Orthodox…affected jargon.”

A more sympathetic approach as to how the terminology came into use by English-speakers is simply that they learned it from contact, direct or indirect, with Russian speakers. The term originated from its use in the Russian language, mirroring its Greek antecedents, and has been transferred into English as such.3

But Professor Yiannias may be on to something. Not that “the term ‘icon writing’ is peculiar to Americans,” but that it is just plain peculiar in English usage, though not without basis in tradition and in logical applications for English-speakers, as we shall see.

An Exploration of Russian Verbs

To get a better understanding of the ambiguity that Blogger David says “lies in the differences between the English and the Russian languages.” I interviewed several native Russian-speakers involved in arts performance and/or art pedagogy. Their comments are seasoned with the awareness that imprecise applications may have been derived from linguistic subtleties in the Russian language, which are not precisely transported into English.

First, here is a series of explanations for Russian usage offered by respondents. The contributors are not identified because they are not speaking authoritatively as iconologists, but simply as witnesses of their own language.

Response 1: In Russian we use verb “to write” (писать), not only in reference to icons but also to any art paintings done as well. For example we say “The portrait/still life is written by …” The verb красить (to paint) in Russian refers to what we do on the walls of a house or a fence.

This is a straightforward comment: “write” is used for creating art; “paint” is used for covering fences. But there are more layers to investigate.

Response 2: Let me put a coin to the issue. For example, here are two phrases in English: “A child paints a picture, and an artist paints a picture.” But in Russian, the phrases will contain different words for the each action, thus a child “paints,” but an artist “writes.” This is a feature of the Russian language and of Old Greek (Koiné) as well, but not English.

The semantic differences are not just that Russians use one word for painting fences and another for working with paint artistically. There is even a semantic difference, as noted above, when referring to play-like activity such as that of a child or a hobbyist and the serious activity of an artist, whether the result is a work of fine art or an icon.

Response 3: The term “to write” is a part of the fine arts vocabulary in Russia. It is used to describe the process of making a painting – any painting, in fact, not just an icon. Using the word “to write” implies a degree of artistry and training. When we talk about serious artworks, a completely new vocabulary kicks in: “to write” instead of “to paint.” That is the way the Russians describe this in Russian among themselves, “This is an icon of the Holy Trinity [written] by Rublev,” or “This is the portrait of Baroness Snivelnosenko [written] by the famous Russian painter Pavel Dirtybrushnikoff.” If a person says something like “he painted a portrait,” he or she would be reprimanded for improper use of language: “One paints a house or a wall, not a portrait, you simpleton!”

My Russian-speaking respondents corroborated further on verb nuances that define two ways to describe the art of picture-making.

Response 4: The verb for “рисовать” (to draw) is used when done on paper with pencils, charcoal etc. The resulting artwork is “рисунок”, a drawing. But even when paint and brushes are used by a child or hobbyist, the verb “рисовать” (to draw) is used. When it comes to a work done by a trained artist, however, a different verb is used, i.e. “писать” (to write), and the product is “картина” a painting. Thus, “писать картину” (to write a painting) should be used.4

Reading and Writing

Adopting Russian expressions in their translation, where separate Russian verbs are related to the activity for which English has only one, accounts for the odd usage of “writing an icon.” That the verbal adoption is only partial, being limited to icons and not applied to all fine art, has to do with the context in which English-speakers encountered the terminology.

For Protestants, especially, and Roman Catholics to the extent they have forgotten their art history, the icon itself is an exotic import – a peculiar thing that needs explaining. A painted surface that is said by Russians to be “written” necessarily implies to English-speakers that it should be read. This may not logically follow from the verb “писать”(to write) in Russian as it does when translated into English, but there are some conceptual benefits to this borrowed verbiage when used figuratively and not stressed too rigidly nor pushed too far.

Western Christians, whether “neo-Eastern Orthodox,” Roman Catholic or Protestant, need only look to their own history of ecclesial art prior to the Renaissance revolution of naturalism to dust off some of the exoticness of icons. The symbolic and analogical language in medieval art of the Roman Church was, for the most part, held in common with ecclesial art of the Orthodox Christian East. In the East this image-language persisted in icons, though not without a courageous struggle against iconoclasm – Byzantine and Soviet.

Illuminated manuscripts and other ecclesial art of the Middle Ages in Western Europe employed the same pictorial language of simultaneous narrative, a horizon-less and three-tiered stage, and a system of symbols as is generally found in Orthodox icons. Modern Westerners, both European and American (perhaps to greater measure), often need an interpreter, so to speak, who can “read” this strange and forgotten language that was represented on a painted surface for Christian civilization (East and West) that understood its meaning without an explainer.

The recent popularity of Eastern Orthodox iconographic art among westerners can be nostalgic and even “affected,” but it is also an earnest longing to become fluent in a language of images from which they have been distanced because it is no longer or barely used in western paintings of religious subjects. It is in this sense that the way Russians (and Greeks) refer to icons as “written” resonates with English-speakers as being appropriate rather than peculiar.

Response 5: Regarding “reading” the painting. During my college days in Russia, we had an instructor of fine arts who taught us how to “read” a painting. She tried to pull us away from a purely sensory perception of art. She said that if we were only to use our senses to appreciate a work of art, we could do so with an abstract painting. For representational works, however, in which images of persons, places and events are depicted, “reading” is a must. Here is the example of such reading:

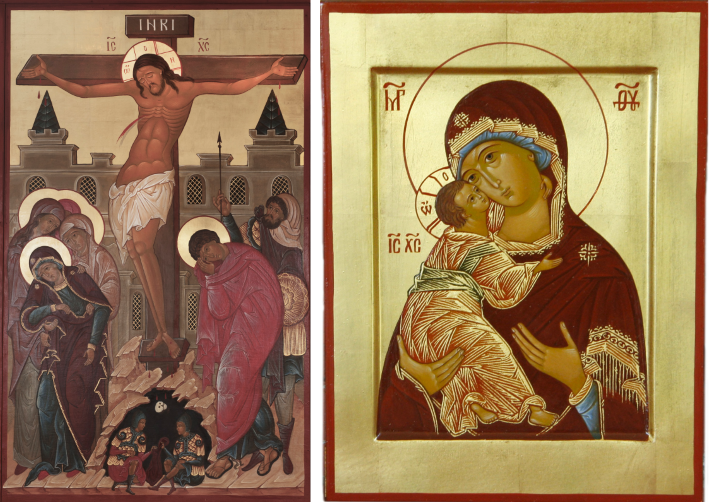

[In one painting I see a man attached to a wooden pole with the beam. There is a woman standing next to him. She has a circle around her head and she is dressed in a purplish cloak. She looks sad. Who is she? Is she a relative? Perhaps, a wife? The naked man also has a round circle around his head, but with odd-looking shapes and symbols placed within the circle. In another painting I see the same woman in the same cloak and with the same circle around her head, but this time she is holding a baby. The baby also has a circle around his head with the same odd markings inside the circle as that of the naked man. She must be his mother.]

The whole semester we did not touch on style or technique. Instead, we “read” the paintings. It was a remarkable exercise, for it allowed us to see far more than we otherwise would. Up to that point, all we had seen was the technique of “how” a painting is executed. But if all you see is the “how,” then artists would paint stills and landscapes and nothing else. The moment a human figure enters the painting, the “who,” “what” and “why” begins. And for that, “reading” the painting is a key to its understanding.

Even in the Engish language, “reading” is not a one-dimensional verb exclusively associated with paper and writing. Do we not speak of “reading” a person’s face or “reading” the clouds for favorable or threatening weather? Do we not also stretch our verbs when we say, “It is written on her face or it is written in the sky”? If English-speakers can take poetic liberty with their verbiage regarding faces and clouds, how is it that the use of “write” is peculiar when it comes to the careful assembly of painted images in the icon intended to convey a theological message?

Here, we leave behind the contrived necessity for adhering to Russian parlance to take on English expressions that have become accidentally useful in understanding the icon. In this context it is possible to support the terminology across linguistic divides.

Icons as Statements of Dogma

The icon is unlike other painted works of art in that its subject matter has an authoritative textual basis, whether Holy Scripture, accepted apocryphal writings or hagiography. This can be said of other examples of religious art, but not to the same degree of faithfulness to textual detail. Icons are, in fact, statements of dogma expressed in images that are painted on a surface. Dogma is received from the Church rather than conceived in the imagination of the artist. Thus, the images in icons should so accurately illustrate and correspond to sacred texts such that an illiterate person can see in the icons what he or she hears read in the services of the Church, i.e. language inscriptions translated into descriptive images.

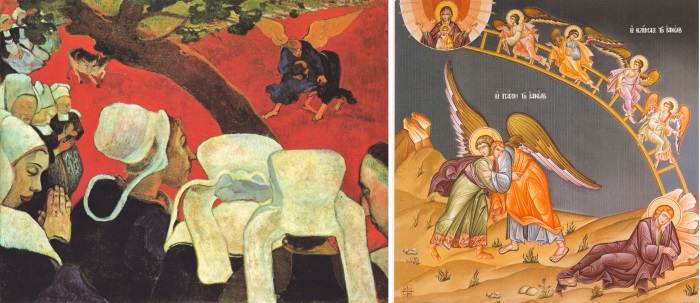

Gauguin’s [vision] of Jacob wrestling with the angel is loosely based on passages found in the Book of Genesis, but without a hint of dogmatic information.

The icon from Holy Hesychasterion of John the Evangelist and Theologian in Thessaloniki, however, represents the text in minute detail: “Taking one of the stones of the place, he put it under his head and lay down in that place to sleep. And he dreamed that there was a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven; and behold, the angels of God were ascending and descending on it!” (Genesis 28:12, 13). “So Jacob was left alone, and a man wrestled with him till daybreak. When the man saw that he could not overpower Jacob, he touched the socket of Jacob’s hip so that his hip was wrenched as he wrestled with the man” (Genesis 32:24, 25).

In the latter example, the images are analogous to a transcription of scriptural text expressed pictorially. Whatever the etymological origins of the Russian verb “писать” (to write), and however inconsistently English-speakers have appropriated it as being unique to icons, it has acquired a metaphorical relevance in the rediscovery of an ecclesial language once commonly understood by all Christians.

When is “Write” Wrong?

Because the artistry of the icon has been widely popularized, examples of its abuse are rife. Celebrated personalities are often presented in iconesque fashion merely to proclaim their ephemeral importance in current culture. By contrast, saying that one “writes” an icon or that an icon is “written” does little harm as long as it is used by English speakers as a metaphorical extrapolation rather than a prescription. “…[A]s any sensible person can see, icons are painted.”

In spite of the fact that the linguistic bastard “to write” was spawned from a collision of languages, its usage has been widely established and will be difficult to abolish. Why all the fuss about an innocuous neologism that helps to explain the visual-load of theological and historical information concerning the life of the Church?

For starters, being purposely odd serves no honest purpose. Saying that one “writes” an icon can be, and sometimes is, “affected jargon” – a kind of NEON Orthodox-speak of the cognoscenti who insist upon the verbiage as the only proper way to refer to the process and the product. As has been demonstrated, Russian use of the term “to write” is a part of their fine arts vocabulary and is used “to describe the process of making a painting – any painting, not just an icon.”

The English language has none of the embedded linguistic references that my Russian respondents have noted which would indicate a preference for the use of “write” over “paint.” A surface filled with theologically didactic delivery can be spoken of as being either painted or written without suffering diminishment. There are no canons requiring or restricting this verbiage in English derived from Russian via Greek and possibly Italian influences (see footnote 4). As one respondent said, “In English, I prefer ‘to paint icons’ and ‘write letters’.”

At the same time, those who police the verbiage to exclude the use of “write, writing, written” in English can be equally totalitarian to the point of correcting Russians. Used metaphorically the adopted terminology (albeit having a specific Russian linguistic basis) can be revelatory to English-speakers as to the particular purpose of icons, that is to articulate through images the textual content to which icons refer. In this sense an icon can be said to be “written” for the right reasons.

The greater risk of implementing derivative iconology-lingo is in harkening to Russian/Greek imports as an opportunity for Gnostic invention. Again, one of my respondents: “The use of the word ‘write’ has absolutely no extra or esoteric connotation. That’s simply the way things are spoken in Russian, and in our language and culture it all makes sense. But when transplanted into English, such direct translations may come across as having some additional hidden meaning.”

Indeed, there is need for concern about [adding] hidden meanings. Popularized distortions of the icon, such as those mentioned above, are common. Camp iconic portraiture seeks its own celebrated ends. But concocting theological airs, using a familiar symbolic system but assigning to it a private interpretation ostensibly “written” in the icon, is as troublesome as it is tortured. Examples of this couched Gnosticism are not easily identified. And, as with many examples of esoterism, the promise of special knowledge is perennially alluring.

One signal that should arouse concern is when the meaning of the process and the product is overworked. When every material component of the icon and every technique used to accomplish it are given a special tag that purportedly reveals not only cosmic mysteries, but also the situation of one’s soul when painting/writing an icon – beware!

Herein, we have come very far from friendly bickering over whether “write” is wrong or right.

FOOTNOTES

1 From an article written by John Yiannias, Ph.D. in Early Christian and Byzantine Art from the University of Pittsburgh. His remarks were originally delivered as an addendum to a talk given at the Orthodox Theological Society in America meeting in Chicago, IL, June 13, 2008.] http://orthodoxhistory.org/2010/06/08/icons-are-not-written/

2 “Is an icon painted or written?” Blogger David, http://russianicons.wordpress.com/tag/jargon/

3 The word iconography comes from the Greek εικονογραφία, a combination of εἰκών (“image”) and γράφειν (“to write”).

4 It is interesting and apropos to the discussion that the Russian word for a painting is ‘kartina’, which is not etymologically Russian, but a loan word from Italian via Latin (cartina, meaning a small piece of paper). Cognates such as ‘chart’ and ‘carta’ (as in Magna Carta) are associated with paper and writing. The use of ‘kartina’, however, is a relatively recent linguistic development in Russian, no earlier than the 17th century.” Since the linguistic root of the word that Russians use for ‘painting’ is related to paper and writing, this may account for why the Russian verb ‘to write’ is used when referring to fine art, including icons.

This essay was first published on the Orthodox Arts Journal.

About the Author

- Mary Lowell is founder and manager of Hexaemeron, a 501c (3) non-profit organization dedicated to sacred arts education. Established in 2003, Hexaemeron has provided training in icon painting for hundreds of students and has recently added courses in ecclesiastical pictorial embroidery. The addition of courses in icon carving (wood and stone) and the mosaic medium is planned for the 2013 season. Although Hexaemeron has been an itinerant school of sacred arts for nearly a decade, it has long been Mary’s goal to create a fully operating apprenticeship program in a fixed location.

- March 3, 2019ArticlesVoyage of the Prodigal: A Poem by Mary Lowell

- December 18, 2018ArticlesReverent Wonder: Two Poems on the Nativity of Christ

- October 1, 2018ArticlesThe Preaching of Columns

- December 12, 2017ArticlesIs “Write” Wrong? A Discussion of Icon Terminology