As a new regime takes office in Washington, utopian dreams are reigning in high fashion. A good time, no doubt, to reflect two classic novels warning of the dystopian danger that invariably arises when utopian fantasies are implemented at the expense of both human nature and truth itself. This essay by Arthur W. Hunt III offers an excellent, comparative primer on these two novels that both, all-too-plausibly, envision the totalitarian horrors resulting from the ruthless imposition of technological planning and calculation on the organic relationships of human beings with one another and with their God.

By Arthur W. Hunt III

Two Novelists Warned Us. Will Fiction Become Fact?

George Orwell’s novel 1984 begins in this way:

It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen. Winston Smith, his chin nuzzled into his breast in an effort to escape the vile wind, slipped quickly though the glass doors of Victory Mansions, though not quickly enough to prevent a swirl of gritty dirt from entering along with him.

Aldous Huxley’s Novel novel Brave New World begins in this way:

A squat grey building of only thirty-four stories. Over the main entrance the words, CENTRAL LONDON HATCHERY AND CONDITIONING CENTRE, and, in a shield, the World State’s motto, COMMUNITY, IDENTITY, STABILITY.

The first smell we encounter in Orwell’s novel is of boiled cabbage. In Huxley’s novel, our first smell is of laboratory chemicals. In Orwell’s novel, everyone is miserable. In Huxley’s, everyone is elated. In Orwell’s novel, compliance is accomplished through pain. In Huxley’s, compliance is accomplished through pleasure. While Orwell speculated that the events in his novel could come to pass in one generation, Huxley was looking six hundred years down the road. Later, Huxley said these events could happen in the twenty-first century.

BOTH DIFFERENT AND SIMILAR

At first glance, one might think the two novels present entirely different prophecies. Neil Postman says as much in the foreword to his book Amusing Ourselves to Death. However, there are actually more similarities between the two works than there are differences. Both novels, of course, are anti-utopias that envision a bleak future rather than a bright one. Both describe the triumph of totalitarianism in a world from which transcendent values have vanished. Both authors sought to address issues hotly debated by intellectuals in the 1930s: What would be the social implications of Darwin and Freud? What ideology would eclipse Christianity? Would the new social sciences be embraced with as much passion as the hard sciences? What would happen if managerial science were taken to the extreme? What would be the long-term effects of modern peacetime advertising? Of wartime propaganda? What would happen to the traditional family? How would class divisions be resolved? How would new technologies shape the future?

Although these questions were on people’s minds in the first half of the twentieth century, they are perhaps more pertinent today than they were then. Both Orwell and Huxley knew that their worlds could be realized under certain conditions. Here are seven characteristics from the novels, which eerily parallel our own times.

WAR AND THE RISE OF TOTALITARIANISM

In 1984 the circumstances that lead to the establishment of totalitarian states include atomic war, the chaos that follows, civil war, a despotic party seizing power, and finally, murderous political purges. Completed just after the Second World War, 1984 imagines what would happen if someone like Hitler succeeded. The three authoritarian superstates of Oceania, Eurasia, and Eastasia engage in perpetual war, which provides constant political fodder with which to manipulate the masses.

In Brave New World there is some early talk about the relevance of biological parents, or what “Our Ford” calls “the appalling dangers of family life.” Then, all is interrupted by war. We should note that when Huxley’s novel was first published, in 1932, the atomic bomb had not yet been dropped. Yet the novel mentions weaponry capable of putting an “enormous hole in the ground.” There are poisonings that infect entire water supplies, and silent anthrax bombs. There is a Nine Years’ War followed by a great Economic Collapse.

Huxley’s brave new world is left at a crossroads. Which would it be: world annihilation due to advances in military might, or the guarantee of safety through sociological control? In the end, the world chooses a highly centralized and efficient authoritarian state, which is able to keep the masses pacified by maintaining a culture of consumption and pleasure. The government makes the masses compliant by conditioning individuals from birth—even before birth—to be a satisfied shopper; everyone is a happy hooter.

And so, in Brave New World there are hatcheries instead of mothers, conditioning centers instead of fathers, plenty of golf courses, and lots of movie theaters. It is a world where every decent girl wears a belt loaded down with ready-to-use contraceptives, a world where everyone is willing to jump in bed at the drop of a hat.

THE PAST ERASED FROM PUBLIC MEMORY

One of the chief slogans in 1984 is “Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.” Of course, in Orwell’s novel, the Party controls the past, and the Party has seen to it that no objective historical record exists. Winston Smith is a government bureaucrat who routinely alters written records to make them fit the Party’s ideology. The past is, in fact, irrelevant, as seen in Oceania’s complete reversal, at the novel’s midpoint, as to who is its enemy: “it became known, with extreme suddenness and everywhere at once, that Eastasia and not Eurasia was the enemy. . . . The Hate continued exactly as before, except that the target had been changed.”

In Brave New World everyone despises the past because it has been declared barbaric. After the Nine Years’ War, there is such a thorough campaign against the past that museums are closed and historical monuments blown up. All the books published before A.F. (After Ford) 150 are suppressed. Children are taught no history. Early in the novel, Mustapha Mond, the Resident Controller of Western Europe, gathers a group of students around him and quotes the wisdom of Our Ford: “History is bunk,” he says. Mond repeats the phrase slowly so everyone will get it: HISTORY IS BUNK. With a wave of the hand, he casually brushes away Ur of the Chaldees, Odysseus, Athens, Rome, Jerusalem, Jesus, King Lear, Pascal. Whisk. Whisk.

THE TRADITIONAL FAMILY UNIT DESTROYED

Drawing from the Hitler Youth and the Soviets’ Young Pioneers, Orwell gives us a society where the child’s loyalty to the state is placed above any devotion to his parents. For example, the character of Parsons, a loyal Party member, is proud of the fact that his own seven-year-old daughter betrayed him after hearing him denounce Big Brother in his sleep. Winston Smith is raised in a camp of orphans, his parents having been killed in the purges. He has only vague and guilt-ridden memories of his mother. His wife is sexually frigid, a condition considered normal by Party standards.

In Huxley’s novel, the biological family does not exist. Prenatal development is controlled in government hatcheries with the use of chemicals. Babies are not born, but decanted. Only the character called Savage has been born in the natural way. Children are conditioned (like Pavlov’s dog) to be ferocious consumers and sexually active. In Brave New World everyone belongs to everyone. Any familial affection is considered gross. “What suffocating intimacies, what dangerous, insane, obscene relationships between members of the family group!” says Mond to his students. “Maniacally, the mother brooded over her children (her children) . . . brooded over them like a cat over its kittens; but a cat that could talk, a cat that could say, ‘My baby, my baby,’ over and over again.”

RATIONAL THOUGHT ERADICATED

In 1984 “war is peace,” “freedom is slavery,” and “ignorance is strength.” Doublethink is the ability to simultaneously hold two opinions that cancel each other out. Indeed, orthodoxy in 1984 is not thinking—not needing to think—to be awake and unconscious at the same time. Orwell knew that if you limited and altered a people’s language—their public discourse—you would also be able to alter their culture. The problem with Winston Smith is that he thinks too much. At his day job he systematically erases the truth from public memory, but at night all he can think about is discovering the real truth. In the end, his powers of reasoning are destroyed through Electro-Convulsive Therapy, which makes him believe two plus two equals five. The Therapy even makes him love Big Brother.

In Brave New World it is Bernard Marx who thinks too much, which makes his associates think his brain received too much alcohol as a fetus. Bernard is contrasted with Lenina Crowne, a true material girl whose deepest affections lie in vibro-vacuum massage machines, new clothes, synthetic music, television, flying, and the drug soma. Whenever Lenina is confronted with a perplexing situation, all she can do is recite trite government phrases: “The more stitches, the less riches,” “Ending is better than mending,” “Never put off till tomorrow the fun you can have today.” Bernard tries to get Lenina to think about things like individual freedom, but she will have none of it and only replies, “I don’t understand.” The characters who think the most, Bernard and Savage, are eventually isolated from the rest of society as misfits.

RELIGIOUS INCLINATIONS RECHANNELED

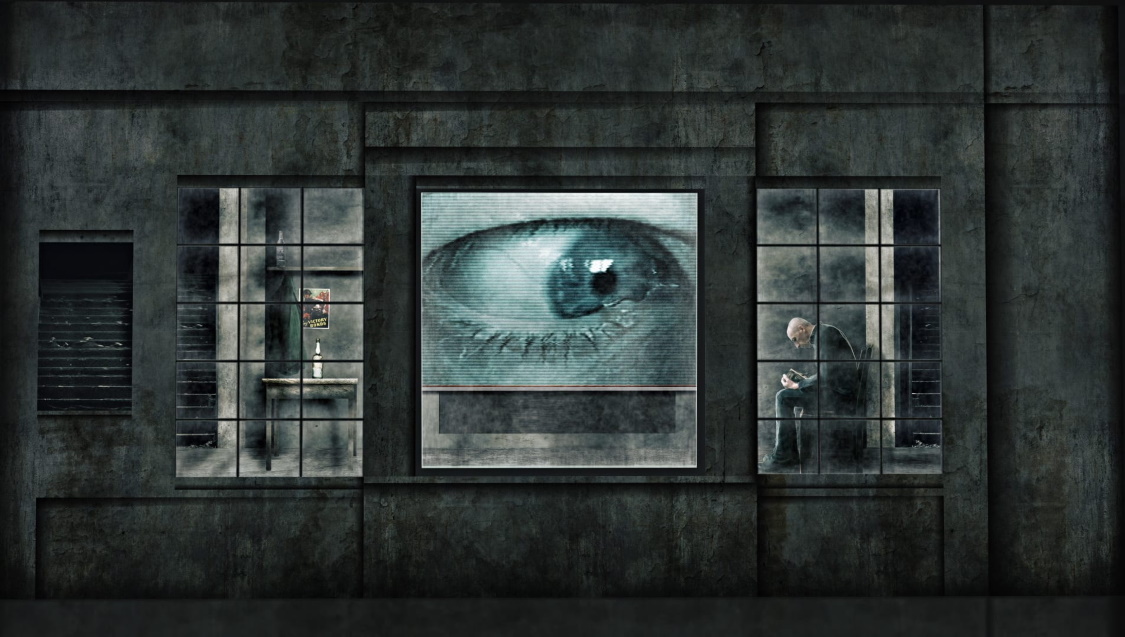

In 1984 Big Brother is omnipresent. His image is found on coins, stamps, books, banners, posters, and cigarette packets. There is a certain religious fervor in the required Two Minutes of Hate and Hate Week rituals, which Orwell modeled after the Nuremberg rallies. The Two Minutes of Hate is a kind of secular church service at which the devil (Goldstein) is railed against and God (Big Brother) is worshiped. The assembly is worked up into a frenzy, jumping up and down and screaming at the tops of their voices at Goldstein until the face of Big Brother appears, “full of power and mysterious calm” and so huge that it almost fills the screen.

In Brave New World the tops of all the church crosses have been cut off to form the letter T (for Technology). Ritual is found in the Solidarity Services and in Orgy-porgy. At the start of each Solidarity Service, the leader makes the sign of the T, turns on the synthetic music, and passes the communion cup of soma. As the service continues, the music gets louder and the drumbeat more pronounced. The congregation chants, “Ford, Ford, Ford.” Everyone dances around the room in a linked circle until the assembly falls into a pagan-style debauch.

TECHNOLOGY USED AS A MEANS OF CONTROL

In 1984 there are two-way telescreens, snooping helicopters, and hidden microphones for spying on people. In Brave New World technology in the form of hatcheries, “feelies,” contraceptives, and soma is used as a conditioning tool. In both novels, efficiency is highly valued. In Orwell’s novel, total control is made possible due to advances in technology. In Huxley’s novel, society has surrendered to the god of technology—technology with a capital T.

AN ELITE RULING CLASS CONTROLS THE MASSES

In 1984 the Inner Party, comprising two percent of the population, wields absolute power. Below this autocratic tip of the iceberg, thirteen percent of the population are trained technicians, and the rest, the Proles, are slave workers. The Inner Party grabs and maintains power for the sake of power alone: O’Brien tells Winston as he tortures him, “The Party seeks power entirely for its own sake. We are not interested in the good of others; we are interested solely in power.” He provides an illustration: “If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever.”

In Brave New World classes have to be created—Alphas, Betas, Deltas, Gammas—to perform the various tasks within society. No one objects to his rank because everyone has been conditioned to think his particular class is the happiest. Nevertheless, Huxley’s world is just as authoritarian as Orwell’s, even if the conditioning is conducted through “suggestions” repeatedly made during “sleep teaching.” As the Director of the hatchery says, “But all these suggestions are our suggestions!”

When Savage realizes that Mustapha Mond also knows lines from Shakespeare, we understand that it is Mond who makes the laws and who can therefore break them as he pleases. It is Mond who sends Bernard off to the islands—islands that the Controller says are “fortunate” because otherwise people who wanted to do such things as think and read Shakespeare would have to be sent to the lethal chamber.

ORWELL AND HUXLEY TODAY

Certainly Postman was correct to say that America more closely resembles the realization of Huxley’s prophecy than Orwell’s. But it is quite possible for any happy-faced tyranny to quickly turn into a sad-faced autocracy. Interestingly, Orwell believed Huxley’s world to be implausible because he maintained that hedonistic societies do not endure, that they are too boring, and that Huxley had not created a convincing ruling class. Nevertheless, the Conditioners, to use C. S. Lewis’s term, are among us today as we witness more intrusion into our lives by the federal government and as we sense a wider influence over our decision-making by corporate entities.

The worlds of Orwell and Huxley are fictitious, but at the time of their publication, both novels were reasonable speculations by gifted men based on conditions already existing in the twentieth century. The passing of two more generations has not removed these conditions; rather, it has only made them more acute. Societies today find their freedom ever more imperiled by such challenges as having to live with weapons of mass destruction, historical dementia, the collapse of the traditional family unit, irrationality, a loss of the Christian ethos, the surrender of the culture to the god of technology, and the concentration of power in the hands of a few. •

This article is based, in part, on a section from chapter 9, “Formula for a Führer,” in the author’s book, The Vanishing Word: The Veneration of Visual Imagery in the Postmodern World (Crossway, 2003).

Source: Salvo 27 (Winter 2013).

About the Author

- Arthur Hunt III is an educator, writer, speaker, and consultant whose wit and wisdom focuses on communication, community, and culture. He is Professor of Communications at the University of Tennessee at Martin (UTM) where he teaches the Public Speaking core course, Honors Public Speaking, Honors Public Speaking in the Rhetorical Tradition, and Communication in Professional Environments. Visit the Arthur Hunt III website.