The Ottoman Empire, Roger Scruton writes, was not composed of nation-states but of creed communities. Peace between the sects could not be ensured by borders, as in Europe, but only by custom. Peace is precarious and requires constant work and architecture is part of that work. When France was given the madate to govern Syria in 1923, the character of the ancient cities of the Mideast began to change. Modernist buildings and the mania for vehicles, roads and motion eroded the native traditions of custom and creed that guided the growth of the Eastern cities for centuries.

One cannot destroy the serene and unostentatious forms of the Levantine city without also jeopardizing the peace that they symbolized and which to a measure they also protected.

Source: American Conservative

By Roger Scruton

Modernist buildings, zoning laws, and a disregard for local custom did more damage than we know.

Unlike visitors to the Middle East today, 19th century travelers in the Levant encountered a deeply settled territory, with villages and towns that were home to many diverse communities. While it would be wrong to romanticize or “orientalize” the social fabric of those communities, which was often torn apart along lines of confession, tribe, and family, there is no doubt that the towns were the fruit of a long experience of settlement and neighborliness.

When the Victorian poet Edward Lear traveled through the Holy Land, sketching thetowns and villages as he went, he left a record of some of the most visually harmonious settlements that the world has known—cities of stone, the roofs blending in undulating canopies, the domes nestling against the sky, the minarets reaching above them in prayer; compact villages with shared stone walls, settled in the countryside like the retreats of ground-nesting birds. Many of these cities remained unchanged well into the 20th century, their alleyways of stone and inward turning houses conveying the sense, so perplexing to a visiting European, that the Arab city is not a public space but an assemblage of private spaces, each dark, secretive, and forbidden harams.

Of course the coastal towns, the big trading centers, and the metropolitan cities developed in the usual 19th century way, with dressed stone facades announcing goods for sale, and classical porches announcing fashionable people. There were tourist resorts and industrial precincts. But inland and away from Western influence the towns retained their ancient character, built like oases, places of shelter where people of many creeds lived side by side in relative harmony.

The Ottoman Empire was not composed of nation-states but of creed communities, some of whom—the Druze, the Alawites, and the Shiites in particular—were not recognized by the Sultan in Istanbul. Peace between the sects could not be ensured, therefore, by borders, as in Europe, but only by custom. Peace so secured is precarious and requires continuous work in order to maintain it. Architecture has been part of that work. The unspoken assumption was that houses should fit together along alleys and streets, that no private house should be so ostentatious as to stand higher than the mosque or the church, and that the city should be a compact and unified place, built with local materials according to a shared vocabulary of forms. Thick walls of stone created interiors that would be cool in summer and warm in winter with the minimum use of energy. The souk was conceived as a public place, embellished appropriately so as to represent the heart of the city, the place where the free trade of goods expressed the free mingling of the communities.

The old souk of Aleppo, tragically destroyed in the current Syrian conflict, was a perfect example of this, the delicate and life-affirming center of a city that has been in continuous habitation for a longer time than any other. That city rose to eminence as the final station on the Silk Road, the place where treasures were unloaded from the backs of camels coming from Mesopotamia onto the carts that would take them to the Mediterranean ports. The fate of this city, which has, in the 21st century, faced destruction for the first time in 5,000 years, is a fitting emblem of what is happening to the Middle East today.

But it is not only civil conflict that has threatened the ancient cities of the Middle East. Long before the current crisis there arrived new ways of building, which showed scant respect for the old experience of settlement and disregarded the unwritten law of the Arab city that no building should reach higher than the mosque, it being the first need of the visitor to spy out the minaret, and so to find the place of prayer. These new ways of building came, like so much else, from the West, first through colonial administration and then through foreign “advisors,” often taking advantage of the insecure land-law of the region, introduced by the Ottoman land code of 1858. By the time France had been granted the mandate to govern Syria in 1923, modernist building types, the mania for roads and motorized “circulation,” the idea that cities should be disaggregated into “zones”—residential, commercial, industrial, and so on—and the obsession with hygiene had all made their destructive mark on the urban fabric.

Those practices—and zoning laws in particular—were to be the topic of Jane Jacobs’s powerful polemic of 1961, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, by which time it was of course too late to save the best of the American heritage. But their impact on the Middle East was every bit as disastrous as their impact on America, and all the more to be regretted given the difficulty of creating viable settlements in a region where religious and cultural conflicts can be managed only in the long term, and only by evolved solutions.

In 1935 a comprehensive plan for Damascus was commissioned by the French authorities from the aptly named René Danger, who began the work of isolating the monuments, clearing the warrens that clung to them, scraping away the sheds and shelters that barnacled the mosques, driving wide hygienic streets through the “insalubrious” areas of the city, and replacing congenial hovels with trees, water, and grass. The residents of the Syrian capital complained vigorously, but to no avail. As in Russia and Germany, the arrival of the totalitarian state was prefaced by the arrival of totalitarian architecture: the plan was welcomed by the Leninist Ba’ath Party when it gained power in the coup of 1963, and became official policy of the new Ba’athist regime.

Damascus has therefore ceased to be the palimpsest on which the histories of four civilizations are inscribed, and today is a modern city, another piece of anywhere. A pattern was set whose influence has now been felt all across the Middle East. Architectural modernism fed into the Arab inferiority complex: concrete high rises, plazas, geometrical patterns, energy-intensive fenestration, sometimes with a mihrab or a dome stuck on in deference to a history that is no longer really believed in—all these have become part of the new vernacular of a hasty urbanization. The basic idea has been to abandon the great tradition of the Ottoman city, with its many communities in their tents of stone, and to “catch up” with the West.

Rarely, in any of this, however, has provision been made for the migrants from the villages, who have been compelled to survive in unplanned and unregulated structures, heaped up around the cities with no thought for how they look or for the character of the public spaces beneath them. Although it would be wrong to pin responsibility for the conflicts that have swept through the Middle East on architecture, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Western town planning and modernist building types, acting upon the indigenous sense of inferiority, have exacerbated the destruction. If you wipe away settlements that have been home for centuries and replace them with faceless blocks that might have been anywhere and are felt to be nowhere, it is not surprising if residents feel that they are already in conflict with their surroundings, and only one step away from conflict with their neighbors as well. The old rabbit-warren city of the Middle East was a conflict-defusing device, a continuous affirmation of neighborhood and settlement. The new city of jerry-built concrete towers is a conflict-enhancing device, a continuous “stand-off” between competing communities on the edge of a place that does not belong to them and to which they in turn cannot belong.

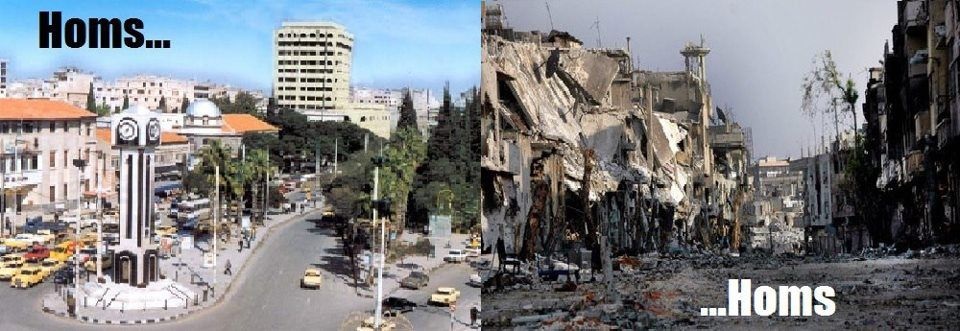

Virtually every expert called upon to pronounce on the conflicts in the Middle East has ignored the role of architecture, with one important exception: the courageous architect Marwa al-Sabouni, whose book, The Battle for Home, tells the story of how the conflict in Syria has overwhelmed her own city of Homs. She shows that you cannot destroy the serene and unostentatious forms of the Levantine city without also jeopardizing the peace that they symbolized and which to a measure they also protected.

The old city of Homs, built of basalt along twisting alleyways, with mosque and church facing each other and sometimes sharing their parts, was treasured by its residents as a common settlement. “Neither mosque nor church,” al-Sabouni writes, “nor any significant building… made a display of its importance…. However, there is a fine line between humility and indifference, and the people of Homs have now crossed that line aggressively….” Writing with clarity and conviction, she shares her experience of this aggression, marking out the contribution made by planning and the built environment, and by the reduction of architectural education to the study of pseudo-Islamic clichés stuck on to banal curtain walls. The story she tells is painful; but it is not a story of escape. True architecture can build a settlement, just as easily as bad architecture can destroy one. Marwa al-Sabouni’s one desire is to stay in her city and remake it as a home to its many communities. We should actively endorse this ambition. For if Syria is not a home to its people, then all of them will be seeking a home elsewhere.

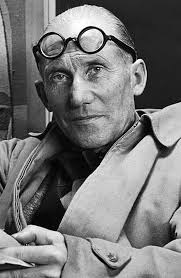

But how do we begin? We should remember that the idea of replacing the organic city of customary styles with cleared spaces and blocks of concrete, while it originated among European intellectuals, was first tried out in the Arab world. Le Corbusier, who had attempted in vain to persuade the city council of Paris to adopt his plan to tear down the entire city north of the Seine and replace it with an assemblage of glass towers, turned his attention to the North African city of Algiers instead, which was at the time under French colonial administration. As architectural advisor to the French Vichy government during the war he was able to overrule the elected mayor of Algiers and impose his will upon the city—though the Allied victory abruptly put an end to his plans.

Le Corbusier’s scheme is still studied and even treated with reverence in modern schools of architecture. It involved erasing the old city from the map, replacing it with great square blocks that negate the Mediterranean coastline and the contours of the landscape, and surmounting the whole with streets along which automobiles fly above the population. No church or mosque has a part in the plan; there are no alleyways or secret corners. All is blank, expressionless, and cold. It is an act of vengeance by the new world against the old: not a project for settling a place, but a project for destroying it, so that nothing of the place remains.

Le Corbusier’s megalomania has fed into the neophilia of many Arab leaders, who believe that they must show themselves to be part of the modern world in Le Corbusier’s way, by replacing everything with some futurist caricature. In addition to Corbusier’s schemes for blocks composed of horizontal planes, therefore, has come the glitzy restaurant style of Dubai, in which vast gadgets, belonging to no known architectural language but looking like kitchen tools discarded by some gigantic celebrity chef, lie scattered among ribbons of motorway. These unadaptable buildings, designed by computers in London offices, and without regard for the place to which they are destined, are symbols of the petrodollar Arabian economy that has replaced the devout communities of fishermen and merchants that once clung to the desert rim. They are gaudy advertisements for all that is most objectionable in the Western way of life, dumped without so much as a by-your-leave among people who have lost the education and the culture that would provide them with the language to respond to the insult. It is difficult not to see such buildings as one part of the provocation offered by the West to the Islamic world.

This brings me back to Marwa al-Sabouni, who is adamant that the strength and identity of the Syria to which she remains committed lies in the conciliation between the communities. Architecture, she believes, has played a part in achieving this, since it has been a primary expression of the sense of place. Care for one’s place is the first move towards accepting the others who reside there. The thoughts “this is our home,” and “we belong here” are peacemaking thoughts. If the “we” is underpinned only by religious faith, and faith defined so as to exclude its historical rivals, then we have a problem. If, however, a resident of Homs can identify himself by the place that he shares with his fellow residents, rather than the faith that distinguishes him, then we are already on the path away from civil war. It is hard to do this when what he understands by “Homs” is a chaos of tower blocks, without proper streets or squares, in which buildings have neither facades nor welcoming doorways, and in which the necessary amenities—shops, schools, mosques, churches—are located miles away on the other side of town. But in Homs as it was, with streets, squares and souk that were the property of everyone, peaceful coexistence, al-Sabouni argues, was the norm. Old Homs was the evolved solution to problems that otherwise risk enduring forever.

It is not possible to rebuild a city like Homs exactly as it was, nor would the residents wish for this. But it is possible to repeat the features that were so important to its peaceful survival: the framed doorways opening onto streets; the windows that observe and the facades that acknowledge the public spaces; the intermingling of shops, ateliers, schools, and homes; the respectful scale and materials of the private structures that refrain from dwarfing the churches and the mosques; the bell towers and minarets that still dominate the skyline in a collective affirmation of faith. Those things can still be achieved, and would be achieved, if the people themselves were to decide how the city should be reconstructed. As everywhere in Syria, however, decisions are made by officials, and officials belong to the great system of Mafia-like corruption that is the true cause of the Syrian conflict, and which has encouraged the Syrian political elite in recent times to look to Russia as its natural ally.

The skeptical reader will say that it is all very well for a Western observer to cherish the organic contours of the traditional Levantine city. But it is surely a fantasy to think that local people see the matter in any such way. Maybe that is so. But we should remember a significant recent instance to the contrary. When the 9/11 hijacker Mohamed Atta traveled from Cairo to Hamburg to study for a master’s degree in urban planning, it was in order to write a thesis on Aleppo. The purpose was not to compose a work of architectural history, but to address one of the most pressing problems confronting the Middle East today, which is the problem of trashy Western architecture, and the alienation of the residents that results from it. Atta wanted to restore a skyline that had been punctured by blunt and shapeless towers; he wanted to discover ways of building that would integrate new streets and modest low-built houses with the existing fabric, respecting both the line of the street and the human materials and scales that had once been the norm.

How well Atta fared in Hamburg, I do not know. But if we should wish to avoid the horrors of that fateful September day—when Atta flew an airplane into a signature work, murdering thousands in the process—we should tread more carefully in the fragile urban ecosystems of the Middle East, actively supporting those who wish to build urban settlements, rather than those who seek to destroy them.

About the Author

- One of our most influential public philosophers, Sir Roger Scruton also holds academic Chairs at Oxford University and the University of St Andrews, as well as the Ethics and Public Policy Center in the United States. He was instrumental in establishing underground academic networks in Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe, for which he was awarded the Czech Republic’s Medal of Merit by President Vaclav Havel. Although his work is wide-ranging, he specializes in aesthetics and political philosophy. He was knighted in 2016 for “services to philosophy, teaching and public education.”

- January 18, 2020ArticlesWhy Beauty Matters

- August 11, 2019ArticlesThe Virtue of Irrelevance: An Essay on Education

- February 1, 2019ArticlesHow Western Urban Planning Fueled War in the Middle East

- February 15, 2018ArticlesBeauty and Desecration: We must rescue art from the modern intoxication with ugliness