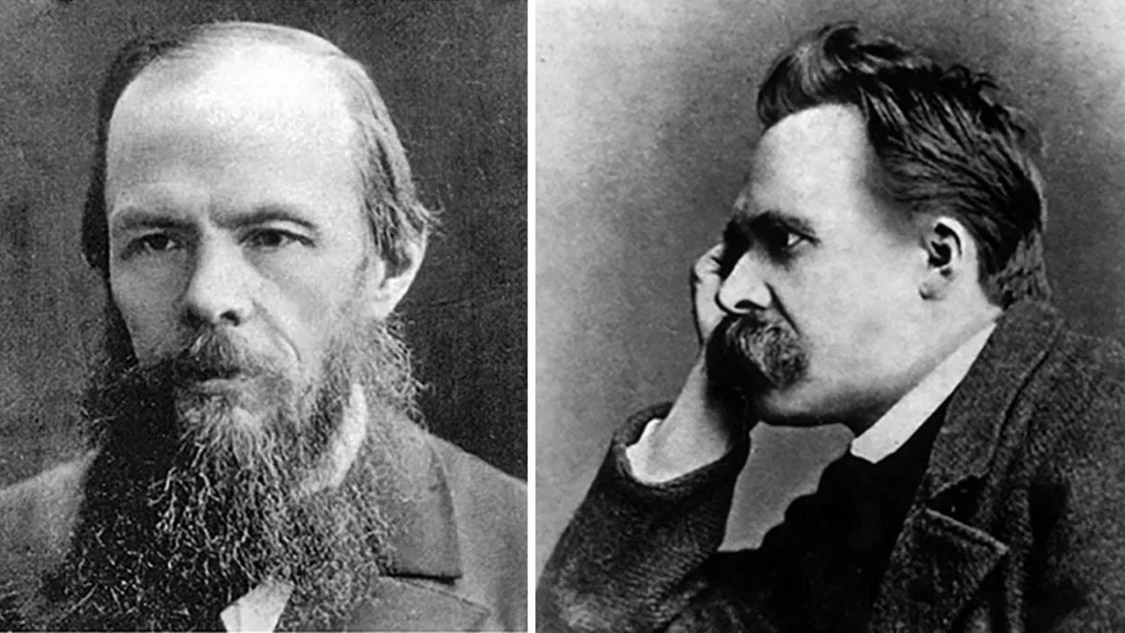

“What is man?” This question shapes all of Dostoevsky’s thought and writing. And perhaps his most important insight is that humanity today is faced with a great choice: between the God-man (Christ) and the Man-God (most visible in Nietzsche’s Übermensch or Overman). Sadly, key figures of Western culture have been increasingly pursuing the second alternative for several centuries, seeking to become divine on their own terms and by their own efforts—striving to re-create the world and human nature itself according to their own will.

Nikolai Berdyaev — along with Frs. Florensky and Bulgakov one of the brightest lights of the Russian Religious Renaissance in the pre-Bolshevik decades — traces this choice (between Man-God and God-man, between Nietzsche and Dostoevsky, between Sodom and the Mother of God) with great insight here, despite his occasional forays into historicism in other parts of the book from which these excerpts are drawn.

By Nikolai Berdyaev

To Dostoevsky is due the striking phrase that “beauty will save the world.” He knew, nothing higher than beauty, it is the supreme expression of ontological perfection, divine— but it is also antinomian, divided, impassioned, terrifying; it has not the godlike calm of the platonic ideal but is scorching, variable, full of tragic conflict.

Beauty did not appear to him in the cosmic order* on the divine plane, but through man, and so it shares the eternal unrest of mankind and is borne along the stream of Heraclitus. We are reminded of Mitya Karamazov’s words*: “Beauty is a terrible and frightening thing. It is terrible because it has not been fathomed, and can’t be fathomed, for God makes nothing but riddles. And in this one, extremes meet and contraries lie down together … Beauty! I can’t bear to think that a man of fine mind and noble heart begins with the ideal of our Lady and ends with the ideal of Sodom. More horrifying still is that a man with the ideal of Sodom in his soul does not renounce the ideal of our Lady; it goes on glowing in his heart, quite genuinely, just as it did when he was young and innocent. Man is too broad; I’d make him narrower.” And again: “Beauty is mysterious as well as terrible. God and the Devil are fighting there, and the battlefield is the human heart.”

In the same way Nicholas Stavroguin* “found the same beauty and an equal delight at the two opposed poles”; there was a similar attraction for him in the ideal of our Lady and the ideal of Sodom. Dostoevsky was profoundly troubled that beauty should be found in both these things at once, and his mind misgave him that there is a satanic element in beauty. His conviction of the antinomy in human nature was so strong that, as we shall see, he found this dark and evil element even in human love

Dostoevsky appeared at the moment when modern times were coming to an end and a new epoch of history was dawning, and it is likely that his consciousness of the inner division of human nature and its movement towards the ultimate depths of being was closely related to this fact. It was given to him to reveal the struggle in man between the God-man and the man-god, between Christ and Antichrist, a conflict unknown to preceding ages when wickedness was seen in only its most elementary and simple forms.

Today the soul of man no longer rests upon secure foundations, everything round him is unsteady and contradictory, he lives in an atmosphere of illusion and falsehood under a ceaseless threat of change. Evil comes forward under an appearance of good, and he is deceived; the faces of Christ and of Antichrist, of man become god and of God become man, are interchangeable.

A large number of contemporary people have “divided minds.” They are the sort of folk whom Dostoevsky displayed to us…It is the destiny of such people over whom the waves of an apocalyptic environment are breaking that Dostoevsky set himself to study, and the light he shed upon them was truly marvelous. Far-reaching discoveries about human nature in general can be made when mankind is undergoing a spiritual and religious crisis, and it was precisely such a time when Dostoevsky appeared upon the scene.

Certainly the Christian soul of the past knew sin and let itself fall under the dominion of Satan, but it did not know that rift in the personality that troubles the people that Dostoevsky studied. In times past evil was more obvious and more simple, and it would be difficult to heal a contemporary soul of its disease by yesterday’s remedies alone. Dostoevsky understood that. He knew all that Nietzsche was to know, but with something added…

The thing which Dostoevsky and Nietzsche knew is that man is terribly free, that liberty is tragic and a grievous burden to him. They had seen the parting of the ways in front of mankind, one road leading to the God-man, Jesus Christ, the other to self-deification, the man-god; they had seen the human soul at the moment when God was withdrawn from it and so undergoing a religious experience of a very special kind, which after a long period of wandering in darkness will produce a new enlightenment. Dostoevsky found that the road to Christ led through illimitable freedom, but he showed that on it also lurked the lying seductions of Antichrist and the temptation to make a god of man. True or not, Dostoevsky had said something new about man.

Dostoevsky’s work marked not merely a crisis in but the defeat of Humanism, and in this his name should be bracketed with Nietzsche’s. They have made it impossible to go back to the old rationalistic Humanism with its self-affirmation and sufficiency, for it is shown that the way, whether to Christ or Antichrist, lies further on and that man cannot remain simply man. Kirilov…wanted to be God; Nietzsche wanted to overcome man as a shame and a disgrace, and turned towards the superman; thus the last end of the humanist cult of man is found to be his own destruction by absorption in the superman. So far from being safeguarded, he is pushed aside as something disgusting, puny, null, fit only to be a means to the superman, that magic idol that devours the men who kneel before him and every other human thing as well.

It may be said then that European Humanism found its term in Nietzsche, who was flesh of its flesh, blood of its blood, and victim of its sins. There was a great difference between him and Dostoevsky who, before him, had shown that the loss of man by the way of self-deification was the inevitable goal of Humanism. Dostoevsky recognized that this deification is illusory, he explored the vagaries of self-will in every direction, and he had another source of knowledge— he saw the light of Christ: he was a prophet of the Spirit. Nietzsche, on the contrary, was dominated by his idea of the superman and it killed the idea of real man in him. Only Christianity has cherished and protected the idea of mankind and fixed the human image for ever and ever.

The human essence presupposes the divine essence; kill God, and at the same time you kill man, and on the grave of these two supreme ideas of God and of man there is set up a monstrous image— the image of the man who wants to be God, of the superman in action, of Antichrist. For Nietzsche there was neither God nor man but only this unknown man-god. For Dostoevsky there was both God and man: the God who does not devour man and the man who is not dissolved in God but remains himself throughout all eternity. It is there that Dostoevsky shows himself to be a Christian in the deepest sense of the word…

[Dostoevsky] showed that the light in our darkness is Christ, that the most abandoned individual still retains God’s image and likeness, that we must love such a one as our neighbor and respect his freedom. Dostoevsky takes us into very dark places but he does not let darkness have the last word; his books do not leave us with an impression of somber and despairing pessimism, because with the darkness there goes a great light. Christ is victorious over the world and irradiates all. Dostoevsky’s Christianity was light-bearing, the Christianity of St. John, and he contributed towards the religion that is to come, the religion of freedom and love, the definitive triumph of Christ’s eternal gospel.

From: Nicholas Berdyaev, Dostoevsky, trans. Donald Attwater, 1957.

* Ed.: Dostoevsky overlooks here many remarkable passages in Dostoevsky’s novels (e.g. The Adolescent and Karamazov) where Dostoevsky eloquently presents the divine beauty to be found in nature.

** Ed.: In Dostoevsky’s novel The Brothers Karamazov

*** Ed.: In Dostoevsky’s novel Demons.

About the Author

-

Nikolai Aleksandrovich Berdyaev (Николай Александрович Бердяев) (1874-1948) was a prominent Russian Orthodox religious philosopher. Berdyaev received an appointment as a philosophy professor at the University of Moscow in 1920, but his independence led to his being jailed twice and finally expelled by the Soviet government in 1922.

He moved to Berlin, where he taught for two years before relocating to Clamart, near Paris. He established the Religious–Philosophical Academy and started a journal dedicated to religious philosophy, Put (The Way). He died in Clamart in 1948.

- July 14, 2019ArticlesDostoevsky or Nietzsche? God-Man or Man-God?