Ayosha, the “angelic brother” of Dostoevsky’s novel. Aloysha the monastic novice. Alyosha the compassihollonate. Alyosha, who has chosen to live only for God. Yes. But Alyosha the depraved? Alyosha the corrupt. . .Alyosha the insect? Christos Yannaras, one of the foremost living philosophers of Europe, through his careful reading of The Brothers Karamazov has seen what many readers of the novel overlook: that the goodness and holiness of its principal character are not traits he possesses by nature, but gift of divine grace that emerge from his struggle “on the edge of the abyss.”

As the Season of Lent begins, our thoughts turn toward repentance. Yannaras maintains here that genuine repentance comes not from forcing our self-image into some prefabricated mold, and then doing our best to convince others and ourselves as well that this is who we are, but from honestly facing our real fallenness and indeed our depravity, our “deep rooted corruption,” and like Alyosha, owning up to the darkness within us, meekly bringing our broken selves before Christ, and seeking healing through His grace.

By Christos Yannaras

- — “I understood it only too well: it’s the innards and the belly that long to love. You put it wonderfully, and I am terrible glad that you have such an appetite for life,” Alyosha cried. “I have always thought that, before anything else, people should learn to love life in this world.”

- — “To love life more than the meaning of life?”

- — “Yes, that’s right. That’s the way it should be; love should come before logic, just as you said. Only then will man be able to understand the meaning of life.”

(Dostoevsky: Brothers Karamazov V.III)

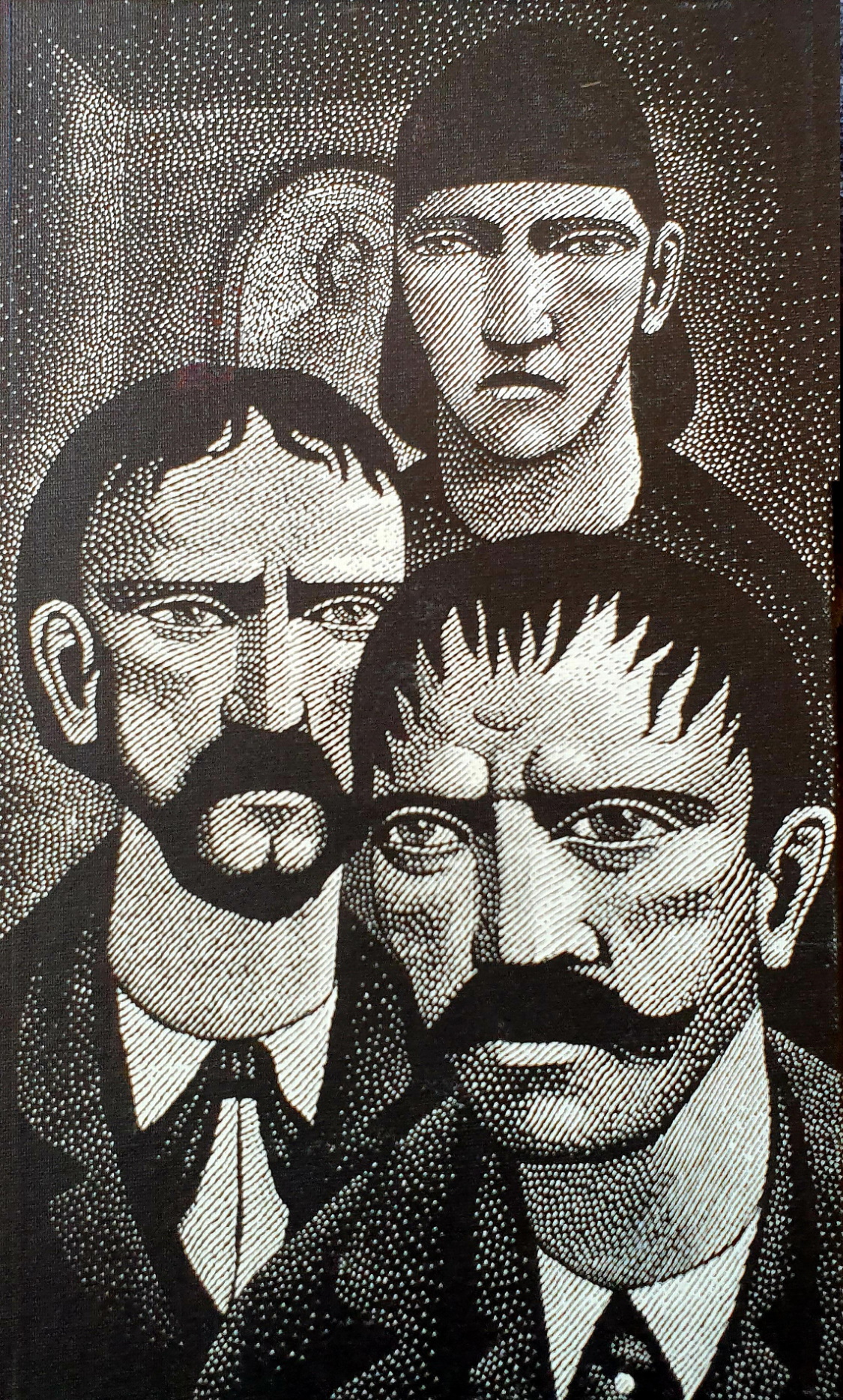

It is hard to start a discussion about a hero for a novel, as famous as Alyosha Karamazov. Most of the people who accompany him throughout the novel are simple and ordinary. Today, however, only wise men speak about Alyosha, and they do so in order to interpret him; all reflection on him tends to be intellectual and rational.

Alyosha has a prophecy to convey, and his prophecy is for all of us. But his words are often difficult, even incomprehensible. What does he mean when he asks us to love life more than its meaning? He himself started to live solely for God, moreover, without compromise. He was nineteen years old when, after giving it serious thought, he became convinced of the existence of God and of immortality; it was natural for him to say to himself, “I want to live to achieve immortality and will accept no compromise.” And he was dressed in a monk’s cassock. Such words spoken at nineteen carry absolute consequences. But how is he able to love life first and before everything?

Perhaps this is the strange prophecy of Alyosha. Throughout The Brothers Karamazov, this uncompromising monk does not stop loving life with a passion, life ineluctably bound to time, life as a natural reality and as a moral task, not even for a second. Every single moment he is a genuine Karamazov. This means a nature able to include any kind of contradiction, to look simultaneously into both abysses: the abyss ahead of us—the one of higher aspirations; and the abyss beneath us—the one of the lowest and most disgusting fall. . . .

“I’m just such an insect, Alyosha,” his brother says, “and the verse applies specifically to me.1 All we Karamazovs are such insects, and one lies in you, too, my angelic brother, and it will stir up storms in your blood, too. Storms, because sensuality is a storm, even more than a storm.”

Alyosha agrees, “I’m just the same as you,” he says. “We’re on he same ladder. I’m on the bottom rung while you’re much higher up, perhaps on the thirteenth rug. That’s how I picture it. But it doesn’t make much difference, it’s the same sort of thing. And once a man has stepped onto the bottom rung, he is sure to climb to the top.”

“ So it would be best not to step onto the ladder at all, wouldn’t it?”

“Well, certainly, if one could help it. . . “

“But can’t you help it?”

“It does not look as if I can.”

These words of Alyosha Karamazov contain no surprise or fear about their truth. Alyosha pursues immortality and God unconditionally, but he does not overlook the fact of the weakness and fallen state of his human nature. This is a deep reconciliation with his human self, the “carnal one under sin” (Rom. 7:14). But what does “reconciliation” mean here? Moralists ought not rush to answer. It is not cause for a decline into the abyss of the lowest and most abominable fall. Even when he leaves the monastery and returns to the world, as Elder Zosima ordered him, Alyosha is still uncompromising in his decision to live for God. “Put it well in your mind, Alexi,” Father Paisios explains to him. “Even if you go back into the world, you should consider it a trial imposed by the Elder. It does not mean you may give in to superficial and vain pleasures.” And Alyosha accepts it. His implacability both in the world and in the monastery is the same. But it is not an implacability that betrays his real self, the weak destructive nature of the Karamazovs. Alyosha, the man of God, is not alien to and different from the Karamazov nature.2 There is a representative scene that gives us the picture of reconciliation. Coming out of the monastery on the night of the Elder’s death, he falls to the earth and hugs it, “and he did not know why he was hugging the earth, why he could not kiss it enough, why he longed to kiss it all. . .He kissed it again and again, drenching it with his tears, vowing to love it always, always.” It is not the drunkenness of a materialist, but a deep reconciliation with soil, with material creation, with his own nature, and is a recapitulation of the whole creation.

Alyosha confuses us; he poses a riddle. This reconciliation with our human self is so rare and foreign for most of us that we have already lost the picture of a whole and integral man, and believe only in division and fragmentation. Spiritual life, as understood by man in our day, splits us and breaks our inner being into two different and conflicting parts so that our unique and real self gets lost. This happens because out moralistic and social education has transmitted to us a criterion of spirituality according to which our fallen human nature, typically laden with so many sins, is unacceptable.

Our moralistic and spiritually conditioned spirituality tends to be a mirror in which we admire ourselves. It helps us build an idealized image of ourselves which we come to regard as true and genuine. We use examples of objective moralist and samples or our good deeds to build our self-admiration. True spirituality, the essential regeneration of man by the Spirit of God, is inaccessible to human criteria and documentary verification. Our moralistic achievements flatter us so much that we believe them to be our true selves. In other words, we are trapped in our self-perception and we do not dare to struggle against our deep-rooted corruption. “I’m just the same as you are,” Alyosha says to his depraved brother. “We’re on the same ladder. I’m on the bottom rung while you’re much higher up, perhaps on the thirteenth rung.” Similar confessions surprise us, usually written by the Fathers of the Church, by ascetics and Saints. We cannot even dare to admit to such things, for we are socially obligated to put forth our spiritual self as a model and example for our fellow man. Our morality is not a fruit of our spiritual regeneration in the grace of God but the need for propriety consistent with our social status and our ethics or with the requirements of participation in a religious form. Under these circumstances, we have acquitted innumerable idols and leaders, of whom society demands perfection and sinlessness according to the masses’ standards of morality. Our world today seeks moral models, people consistent with the principles of the prevailing moral system. It is the demand of the times, the demand of any age, because masses cannot live without idols. Furthermore, human egotism feeds on the admiration and adoration of the masses.

Morality, however, is not the problem. Morality as the primary manifestation of religion is a means of limiting the promiscuity of those people who are religious only in appearance. But when a gloss replaces another gloss, the problem becomes even more complicated. Christianity projects a morality: Jesus Christ is not only the incarnate God but also the perfect moral man. Christianity is not, however, as people of our day think, only morality. The essential content of faith—the salvation unto grace, the reorientation of our depraved nature in the humanity of the New Adam, the defeat of death, and the redemption of the human person’s integrity into a life not bound by place, time, and corruption—all these things are unknown and incomprehensible realities for the Christianity common today. We are responsible for having cultivated a social perception of Christianity. We built it on a moralistic representation of the “perfect man,” nurturing an overgrown super-ego, and we are unable to see the human reality of our fall and corruption, and our need for the grace of God.

How is it possible then for Alyosha to live among us, this inconceivable Alyosha, who dares to confess his weakness and sinfulness, who dares to be what he is, a real Karamazov and not a moral model for the masses? Alyosha is scandal according to the standards of our common Christianity, as he balances on the edge of the abyss and fights in the open with the demon of sensuality, the demon of the Karamazovs, without revolting against or preaching to even the most abject of men, who struggle like Alyosha on the edge of the abyss. For such a scandal, the Grand Inquisitor would burn him first, together with his beloved Elder Zosimas who, even as a dead man whose body dared to disintegrate, is indifferent to the scandal of the masses. Alyosha and Zosimas did not try to hide the fact that their human nature is subject to decay, and moralistic people cannot bear such a scandal.

Throughout the novel, Alyosha Karamazov needs neither interpretations not defense. He is what he is, a genuine man, the kind of man we meet in the Bible. Only from Holy Scripture could Dostoevsky create such a hero. Let us recall the throng of holy publicans and prostitutes in the Scriptures who do not display their perfect moral selves before God, as though deserving to be rewarded by His Justice. Rather, they reveal a conscience of the utmost sinful self, which yearns for His love. “Let her many sins be forgiven because she loved much,” only because she loved.3 Alyosha is the same. He loves God so much, with no compromise, and only He can save his undisciplined Karamazov nature. This is why Alyosha is so wholly reconciled with his human self. He believes that this self is the reason for Christ’s gif of salvation. This faith is already a reality in the new creation of the Church. “For not the powerful but those who lay hurt are in need of a doctor.”4 Thus, blessed are the ones who lay hurting. . .Look around you, how miserable and unredeemed are the presumed morally justified leaders of the masses; how many complexes they have, how distant they are from life and people. They have never had a need to cry desperately to God asking for the redemption of their depraved hearts. They have never perceived the depravity of their hearts. Morally immaculate, they are models for the masses in the most ridiculous formalities and details. These perfect statues of moralistic beauty remain frozen and soulless in their smug, moralistic self-sufficiency.

FOOTNOTES

- The verse applies specifically to me: Aloysha’s brother Mitya has just recited a passage from Schiller’s Ode to Joy that ends with the lines:

All being drinks the mother-

Of joy from Nature’s holy bosom;

And good and evil both pursue

Her steps that strew the rose’s blossom.

The brimming cup, love’s loyalty

In heaven the cherub looks on God.

In heaven the cherub looks on God!up, love’s loyalty

Joy gives to us; beneath the sod,

To insects—sensuality; - Alyosha, the man of God: “Alyosha” is the Russian diminutive for “Alexei,” a name taken from the Venerable Alexios, the Man of God. St Alexios, a fourth century Roman of noble parentage, felt called to leave behind wealth and family and even his bride in response to a vision of St Paul reciting Christ’s words: “He that loveth father or mother more than me is not worthy of me.” After travelling to Syria, where he lived as a beggar and a silent monk, he found his way back to his family, with whom he lived anonymously as a servant outside the house. On the day of his death, at the Liturgy attended by the emperor, voices from heaven were heard saying “The Man of God comes forth from the body; have him pray for the city, that you may remain untroubled.” The Life of St Alexis the Man of God was popular in Russia and was loved by Dostoevsky, who named his son Alexei or Alyosha. Upon the death of Alysoha at only three years of age, the grieving Dostoevsky (accompanied by a young friend, the philosopher Soloviev) went as a pilgrim to Optina Monastery in search of consolation. It was there that he met repeatedly with Elder Ambrose, who inspired the figure of Elder Zosima, the spiritual father of the character Alyosha in Dostoevsky’s novel.

- Luke 7:47: “Therefore I say to you, her sins, which are many, are forgiven for she loved much. But to whom little is forgiven, the same loves little.”

- Matthew 9:12: “When Jesus heard that, He said to them, ‘Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who sick.’”

Source: Christos Yannaras, The Meaning of Reality: Essays on Existence and Communion, Eros and History, edited by Fr Gregory Edwards and Herman A. Middleton (Los Angeles: Sebastion Press, 2011) pp. 1-5. All footnotes have been added by the editors of Another City.

Yannaras’ The Meaning of Reality, from which this essay is taken, along with his classic study of basic Christian doctrines in the Orthodox Church, The Ecclesial Experience, are both available at St. Sebastian Orthodox Press.

About the Author

-

Christos Yannaras or Chrestos Giannaras, (Greek: Χρήστος Γιανναράς), is Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at the Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences in Athens and a philosopher and theologian of the Orthodox Church of Greece.

The main area of Professor Yannaras' work is in the study and research of the differences between Greek and Western European philosophy and tradition. These differences are not limited solely at the level of theory, but also define a mode (praxis) of life.

- March 19, 2021ArticlesA Reference to Alyosha Karamazov