The essence of any religion is contained in the spiritual life, which is its most sacred side. Entry into this life demands not only good intentions, but also knowledge of the laws of spiritual life. But to acquire this knowledge in an age of spiritual confusion requires clear guidance. The writings of the nineteenth century ascetic and theologian, St Ignatius Brianchaninov, are based upon his scrupulous study of patristic writings, tried in the furnace of personal ascetical experience. They provide a kind of Orthodox ascetical encyclopedia clarifying the most important questions of spiritual life, including the dangers that can be met along the way. They set forth the patristic experience of the knowledge of God as applied to the particular psychology and special weaknesses of people living in a secular age, making his writings exceptionally valuable for modern-day Christians.

Source: Orthodox Christian

By Alexei Ilyich Osipov

The essence of any religion is contained in the spiritual life, which is its most sacred side. Any entrance into this life demands not only zeal, but also knowledge of the laws of spiritual life. Zeal not according to knowledge is a poor helper, as we know. Vague, indistinct conceptions of this main side of religious life lead the Christian, and especially the ascetic, to grievous consequences; in the best case to fruitless labors, but more often to self-opinion and spiritual, moral, and psychological illness. The most widespread mistake in religious life is the substitution of its spiritual side (fulfillment of the Gospel commandments, repentance, struggle with the passions, love for neighbor) with the external side—fulfillment of Church customs and rites. As a rule, such an approach to religion makes a person outwardly righteous, but inwardly a prideful Pharisee, hypocrite, and rejected by God—a “saint of satan.” Therefore it is necessary to know the basic principles of spiritual life in Orthodoxy.

Of great help in this is an experienced guide who sees the human soul. But such guides were very rare even in ancient times, as the Fathers testify. It is even more difficult to find such guides in our times. The Holy Fathers foresaw that in the latter times there would be a famine of the word of God (even though the Gospels are now printed abundantly!) and instructed sincere seekers in advance to conduct their spiritual lives by means of “living under the guidance of patristic writings, with the counsel of their contemporary brothers who are successfully progressing [in spiritual life].”

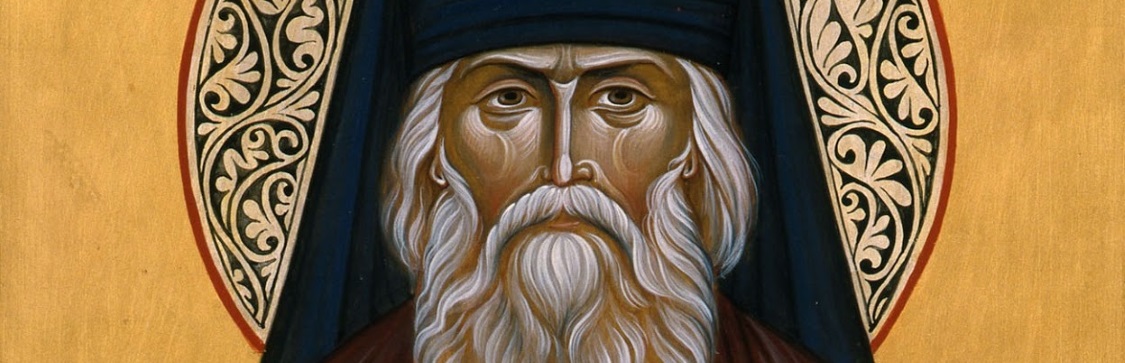

These words belong to one of the most authoritative Russian spiritual instructors and writers of the nineteenth century, Saint Ignatius Brianchaninov (1807–1867). His writings are a kind of Orthodox ascetical encyclopedia representing those very patristic writings, but are of particular value to the modern-day Christian.

This value comes from the fact that his writings are based upon his scrupulous study of patristic writings, tried in the furnace of personal ascetical experience, and provide a clear exposition of all the most important questions of spiritual life, including the dangers that can be met along the way. They set forth the patristic experience of the knowledge of God applicable to the psychology and strength of people living in an epoch closer to us both in time and degree of secularization.1

Here we shall present only a few of the more important precepts of his teaching on the question of correct spiritual life.

I. Correct Thoughts

“People usually consider thought to be something of little importance, and therefore they are very undiscerning in their acceptance of thoughts. However, everything good comes from the acceptance of correct thoughts, while everything evil comes from the acceptance of deceitful thoughts. Thought is like the helm of a ship. A small wheel and an insignificant board dragging behind a great vessel decide its direction and, more often than not, its fate” (4:509).2 Thus wrote Saint Ignatius, emphasizing the exceptional significance that our thoughts, views, and theoretical knowledge as a whole have for spiritual life. Not only correct dogmatic faith and Gospel morals, but also knowledge and rigorous observation of spiritual laws determine success in the complex process of true rebirth of the passionate, “fleshly” (Rom 8:5), old man (Eph 4:22) into the new man (Eph 4:24).

However, a theoretical understanding of this question is not as simple as it would seem at first glance. The many different so-called “spiritual ways of life” that are now being offered to man from all sides are one of the illustrations of the complexity of this problem.

Therefore, a task of the utmost importance arises: finding the more essential indications and qualities of true spirituality, which would allow one to differentiate it from all the possible forms of false spirituality, mysticism, and prelest. This has been sufficiently explained by the Church’s 2,000 years of experience in the person of its saints; but modern man, raised in a materialistic and unspiritual civilization, runs up against no little difficulty in assimilating it.

Patristic teachings have always corresponded to the level of those to whom they are directed. The Fathers of the Church never wrote “just for the sake of it” or “for science.” Many of their counsels, directed at ascetics of high contemplative life and even to so-called beginners, no longer even remotely correspond to the spiritual strength of the modern Christian. Furthermore, the variety, ambiguity, and at times even contradictoriness of these counsels that naturally occur due to the varying spiritual levels of those who seek them can disorient the inexperienced. It is very difficult to avoid these dangers when studying the Holy Fathers without knowing at least the more important principles of spiritual life. On the other hand, a correct spiritual life is unthinkable without patristic guidance. Before this seemingly insurmountable impasse, we can see the full significance of the spiritual inheritance of those fathers, most of whom are closer to us in time, who “restated” this earlier patristic experience of spiritual life in a language more accessible to a modern man little acquainted with this life, who usually has neither a capable guide nor sufficient strength.

The works of Saint Ignatius Brianchaninov are among the best of these “restatements,” which provide an impeccably reliable “key” to understanding the teachings of great laborers in the science of sciences—the ascetics.

II. What is the Meaning of Faith in Christ?

Here is what Saint Ignatius writes about this:

The beginning of conversion to Christ consists in coming to know one’s own sinfulness and fallenness. Through this view of himself, a person recognizes his need for a Redeemer, and approaches Christ through humility, faith, and repentance (4:277). He who does not recognize his sinfulness, fallenness, and peril cannot accept Christ or believe in Christ; he cannot be a Christian. Of what need is Christ to the person who himself is wise and virtuous, who is pleased with himself, and considers himself worthy of all earthly and heavenly rewards? (4:378).

Within these words the thought involuntarily draws attention to itself that the awareness of one’s own sinfulness and the repentance proceeding from it are the first conditions for receiving Christ — that is, the belief that Christ came, suffered, and was resurrected is the beginning of conversion to Christ, for the devils also believe, and tremble (Jas 2:19), and from the knowledge of one’s sinfulness comes true faith in Him.

The holy hierarch’s thought shows the first and main position of spiritual life, which so often slips away from the attention of the faithful and shows the true depth of its Orthodox understanding. The Christian, as it happens, is not at all the one who believes according to tradition or who is convinced of the existence of God through some form of evidence, and, of course, the Christian is not at all one who goes to Church and feels that he is “higher than all sinners, atheists, and non-Christians.” No, the Christian is the one who see his own spiritual and moral impurity, his own sinfulness, sees that he is perishing, suffers over this, and therefore he is inwardly free to receive the Savior and true faith in Christ. This is why, for example, Saint Justin the Philosopher wrote, “He is the Logos in Whom the whole human race participates. Those who live according to the Logos are Christians in essence, although they consider themselves to be godless: such were Socrates and Heraclites, and others among the Hellenes.… In the same way those who lived before us in opposition to the Logos were dishonorable, antagonistic to Christ … while those who lived and still live according to Him are Christians in essence.”3 This is why so many pagan peoples so readily accepted Christianity.

On the contrary, whoever sees himself as righteous and wise, who sees his own good deeds, cannot be a Christian and is not one, no matter where he stands in the administrative and hierarchical structure of the Church. Saint Ignatius cites the eloquent fact from the Savior’s earthly life that He was received with tearful repentance by simple Jews who admitted their sins, but was hatefully rejected and condemned to a terrible death by the “intelligent,” “virtuous,” and respectable Jewish elite—the high priests, Pharisees (zealous fulfillers of Church customs, rules, etc.), and scribes (theologians).

They that be whole need not a physician, but they that are sick (Mt 9:12), says the Lord. Only those who see the sickness of their soul and know that it cannot be cured through their own efforts come to the path of healing and salvation, because they are able to turn to the true Doctor Who suffered for them—Christ. Outside of this state, which is called “knowing oneself” by the Fathers, normal spiritual life is impossible. “The entire edifice of salvation is built upon the knowledge and awareness of our infirmity,” writes Saint Ignatius (1:532). He repeatedly cites the remarkable words of Saint Peter of Damascus: “The beginning of the soul’s enlightenment and mark of its health is when the mind begins to see its own sins, numbering as the sands of the sea” (2:410).

Therefore, Saint Ignatius exclaims over and over,

Humility and the repentance which comes from it are the only conditions under which Christ is received! Humility and repentance are the only price by which the knowledge of Christ is purchased! Humility and repentance make up the only moral condition from which one can approach Christ, to be taken in by Him! Humility and repentance are the only sacrifice which requites, and which God accepts from fallen man (cf. Ps 50:18–19). The Lord rejects those who are infected with pride, with a mistaken opinion of themselves, who consider repentance to be superfluous for them, who exclude themselves from the list of sinners. They cannot be Christians (4:182–183).

III. Know Yourself

How does a person obtain this saving knowledge of himself, his “oldness,” a knowledge which opens to him the full, infinite significance of Christ’s Sacrifice? Here is how Saint Ignatius answers this question.

I do not see my sin because I still labor for sin. Whoever delights in sin and allows himself to taste of it, even if only in his thoughts and sympathy of heart, cannot see his own sin. He can only see his own sin who renounces all friendship with sin; who has gone out to the gates of his house to guard them with bared sword—the word of God; who with this sword deflects and cuts off sin, in whatever form it might approach. God will grant a great gift to those who perform this great task of establishing enmity with sin; who violently tear mind, heart, and body away from it. This gift is the vision of one’s own sins (2:122).

In another place he gives the following practical advice: “If one refuses to judge his neighbors, his thoughts naturally begin to see his own sins and weaknesses which he did not see while he was occupied with the judgment of his neighbors” (5:351). Saint Ignatius expresses his main thought on the conditions for self-knowledge by the following remarkable words of Saint Symeon the New Theologian: “Painstaking fulfillment of Christ’s commandments teaches man about his infirmity” (4:9); that is, it reveals to him the sad picture of what really resides in his soul and what actually happens there.

The question of how to obtain the vision of one’s sins, or the knowledge of one’s self, one’s old man, is at the center of spiritual life. Saint Ignatius beautifully showed its logic: only he who sees himself as one perishing has need of a Savior; on the contrary, the “healthy” (cf. Mt 9:12) have no need of Christ. Therefore, if one wants to believe in Christ in an Orthodox way, this vision becomes the main purpose of his ascetic labor, and at the same time, the main criteria for its authenticity.

IV. Good Deeds

On the contrary, ascetic labors, or podvigs -— and any virtues that do not lead to such a result are in fact false podvigs -— and life becomes meaningless. The Apostle Paul speaks of this in his epistle to Timothy, when he says, And if a man also strive for masteries, yet is he not crowned, except he strive lawfully (2 Tm 2:5). Saint Isaac the Syrian speaks about this even more specifically: “The recompense is not for virtue, nor for toil on account of virtue, but for humility which is born of both. If humility is lacking, then the former two are in vain.”4

This statement opens yet another important page in the understanding of spiritual life and its laws: neither podvigs nor labors in and of themselves can bring a person the blessings of the Kingdom of God, which is within us (Lk 17:21), but only the humility which comes from them. If humility is not gained, all ascetic labors and virtues are meaningless. However, only labor in the fulfillment of Christ’s commandments teaches man humility. This is how one complex theological question on the relationship between faith and good works in the matter of salvation is explained.

Saint Ignatius devotes great attention to this question. He sees it in two aspects: first, in the sense of understanding the necessity of Christ’s sacrifice; and second, with respect to Christian perfection. His conclusions, proceeding as they do from patristic experience, are not ordinary subjects for classroom theology.

He writes, “If good deeds done according to feelings of the heart brought salvation, then Christ’s coming would have been superfluous” (1:513). “Unfortunate is the man who is satisfied with his own human righteousness, for he does not need Christ” (4:24). “Such is the natural quality of all bodily podvigs and visible good deeds. If we think that doing them is our sacrifice to God, and not just reparation for our immeasurable debt, then our good deeds and podvigs become the parents in us of soul-destroying pride” (4:20).

Saint Ignatius even writes,

The doer of human righteousness is filled with self-opinion, high-mindedness, and self-deception … he repays with hatred and revenge anyone who dares to open his mouth to pronounce the most well-founded and good-intentioned contradiction of his righteousness. He considers himself worthy, most worthy of both earthly and heavenly rewards (4:47).

From this we can understand the saint’s call, which is:

Do not seek Christian perfection in human virtues. It is not there; it is mystically preserved in the Cross of Christ (4:477–478).

This thought directly contradicts the widespread belief that so-called “good deeds” are always good and aid us in our salvation, regardless of what motivates a person to do them. In reality, righteousness and virtue of the old and new man are not mutually supplementary, but rather mutually exclusive. The reason for this is sufficiently obvious. Good works are not an end, but a means for fulfilling the supreme commandment of love. But they can also be done calculatingly, hypocritically, and out of ambition and pride. (When a person sees the needy but instead gilds domes on churches, or builds a church where there no real need of one, it is clear that he is not serving God, but his own vanity.) Deeds that are not done for the fulfillment of the commandments blind a person by their significance, puff him up, make him great in his own eyes, exalt his ego, and thereby separate him from Christ. But the fulfillment of the commandments of love for neighbor reveals a person’s passions to himself, such as: man-pleasing, self-opinion, hypocrisy, and so on. It reveals to him that he cannot do any good deed without sin. This humbles a person and leads him to Christ. Saint John the Prophet said, “True labor cannot be without humility, for labor in and of itself is vain and accounted as nothing.”5

In other words, virtues and podvigs can also be extremely harmful if they are not founded upon the knowledge of hidden sin in the soul and do not lead to an even deeper awareness of it. Saint Ignatius instructs, “One must first see his sin, then cleanse himself of it with repentance and attain a pure heart, without which it is impossible to perform a single good deed in all purity” (4:490). “The ascetic,” he writes, “has only just begun to do them [good deeds] before he sees that he does them altogether insufficiently, impurely.… His increased activity according to the Gospels shows him ever more clearly the inadequacy of his virtues, the multitude of his diversions and motives, the unfortunate state of his fallen nature.… He recognizes his fulfillment of the commandments as only a distortion and defilement of them” (1:308–309). Therefore, the saints, he continues, “cleansed their virtues with floods of tears, as if they were sins” (2:403).

V. Untimely Dispassion is Dangerous

Let us turn out attention to yet another important law of spiritual life. It consists in “the like interrelationship of virtues and of vices” or, to put it another way, in the strict consequentiality and mutual conditioning of the acquisition of virtues as well as the action of passions. Saint Ignatius writes, “Because of this like relationship, voluntary submission to one good thought leads to the natural submission to another good thought; acquisition of one virtue leads another virtue into the soul which is like unto and inseparable from the first. The reverse is also true: voluntary submission to one sinful thought brings involuntarily submission to another; acquisition of one sinful passion leads another passion related to it into the soul; the voluntary committing of one sin leads to the involuntary fall into another sin born of the first. Evil, as the fathers say, cannot bear to dwell unmarried in the heart” (5:351).

This is a serious warning! How often do Christians, not knowing this law, carelessly regard the so-called “minor” sins, committing them voluntarily -— that is, without being forced into them by passion. And then they are perplexed when they painfully and desperately, like slaves, involuntarily fall into serious sins which lead to serious sorrows and tragedies in life.

Just how necessary it is in spiritual life to strictly observe the law of consequentiality is shown by the following words of a most experienced instructor of spiritual life, Saint Isaac the Syrian (Homily 72), and cited by Saint Ignatius: “It is the good will of the most wise Lord that we reap our spiritual bread in the sweat of our brow. He established this law not out of spite, but rather so that we would not suffer from indigestion and die. Every virtue is the mother of the one following it. If you leave the mother who gives birth to the virtue and seek after her daughter, without having first acquired the mother, then these virtues become as vipers in the soul. If you do not turn them away, you will soon die” (2:57–58). Saint Ignatius warns sternly in connection with this, “Untimely dispassion is dangerous! It is dangerous to enjoy Divine grace before the time! Supernatural gifts can destroy the ascetic who has not learned of his own infirmity” (1:532).

These are remarkable words! To someone who is spiritually inexperienced the very thought that a virtue can be untimely, never mind deadly to the soul, “like a viper,” would seem strange and almost blasphemous. But such is the very reality of spiritual life; such is one of its strictest laws, which was revealed by the vast experience of the saints. In the fifth volume of his Works, which Saint Ignatius called An Offering to Contemporary Monasticism, in the tenth chapter entitled, “On caution in the reading of books on monastic life,” he states openly, “The fallen angel strives to deceive monks and draw them to destruction, offering them not only sin in its various forms, but also lofty virtues that are not natural to them” (5:54).

VI. Correct Prayer

These thoughts have a direct relationship to understanding a very important Christian activity: prayer. Saying as do all the saints that “Prayer is the mother of the virtues and the door to all spiritual gifts” (2:228), Saint Ignatius emphatically points to the conditions that must be met in order to make prayer the mother of the virtues. Violating these conditions makes prayer fruitless at best; but more often, it makes it the instrument of the ascetic’s precipitous fall. Some of these conditions are well known. Whoever does not forgive others will not be forgiven himself. “Whoever prays with his lips but is careless about his heart prays to the air and not to God; he labors in vain, because God heeds the mind and heart, and not copious words,” says Hieromonk Dorotheus, a Russian ascetic for whom Saint Ignatius had great respect (2:266).

However, Saint Ignatius pays particular attention to the conditions for the Jesus Prayer. In light of its great significance for every Christian, we present a brief excerpt from the remarkable article by Saint Ignatius, “On the Jesus Prayer: A Talk with a Disciple.”

In exercising the Jesus prayer there is its beginning, its gradual progression, and its endless end. It is necessary to start the exercise from the beginning, and not from the middle or the end.…

Those who begin in the middle are the novices who have read the instructions … given by the hesychastic fathers … and accept this instruction as a guide in their activity, without thinking it through. They begin in the middle who, without any sort of preparation, try to force their minds into the temple of the heart and send up prayers from there. They begin from the end who seek to quickly unfold in themselves the grace-filled sweetness of prayer and its other grace-filled actions.

One should begin at the beginning; that is, pray with attention and reverence, with the purpose of repentance, taking care only that these three qualities be continually present with the prayer.… In particular, most scrupulous care should be taken to establish morals in accordance with the teachings of the Gospels.… Only upon morality brought into good accord with the Gospel commandments … can the immaterial temple of God-pleasing prayer be built. A house built upon sand is labor in vain—sand is easy morality that can be shaken (1:225–226).

From this citation it can be seen how attentive and reverently careful one must be with respect to the Jesus prayer. It should be prayed not just any way, but correctly. Otherwise, its practice will not only cease to be prayer, it can even destroy the one practicing it. In one of his letters, Saint Ignatius talks about how the soul should be disposed during prayer: “Today I read the saying of Saint Sisoes the Great which I have always especially liked; a saying which has always been according to my heart. A certain monk said to him, ‘I abide in ceaseless remembrance of God.’ Saint Sisoes replied to him, “That is not great; it will be great when you consider yourself worse than all creatures.’ The ceaseless remembrance of God is a great thing!” Saint Ignatius continues. “But this is a very dangerous height when the ladder that leads to it is not founded upon the sturdy rock of humility” (4:497).

(In connection with this it must be noted that “the sign of ceaseless and self-moving Jesus prayer is by no means a sign that the prayer is grace-filled, because [such qualities] do not guarantee … those fruits that always indicate that it is grace-filled.” “Spiritual struggle, the result and purpose of which is the acquisition of HUMILITY … is [in this case] substituted by some [interim] purpose: the acquisition of ceaseless and self-acting Jesus prayer, which … is not the final goal, but only one means of attaining that goal.”6)

From: Alexei I. Osipov, The Search for Truth on the Path of Reason (Sretensky Monastery, Pokrov Press, 2009) 238-240.

Translation by Nun Cornelia (Rees)